Pan Tadeusz

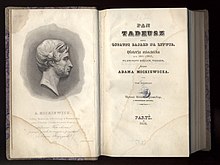

Title page of the first edition | |

| Author | Adam Mickiewicz |

|---|---|

| Original title | Pan Tadeusz, czyli ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem |

| Translator | Maude Ashurst Biggs, Watson Kirkconnell, George Rapall Noyes, Kenneth R. Mackenzie, Marcel Weyland, Bill Johnston |

| Language | Polish |

| Genre | Epic poem |

| Set in | Russian Partition, 1811–12 |

| Publisher | Aleksander Jełowicki |

Publication date | 28 June 1834 |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1885 |

| 891.8516 | |

| LC Class | PG7158.M5 P312 |

Original text | Pan Tadeusz, czyli ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem at Polish Wikisource |

| Translation | Pan Tadeusz at Wikisource |

| Pan Tadeusz | |

|---|---|

| Form | Epic poem |

| Meter | Polish alexandrine |

| Rhyme scheme | in couplets |

| Lines | 10,000 |

Pan Tadeusz (full title: Sir Thaddeus, or the Last Foray in Lithuania: A Nobility's Tale of the Years 1811–1812, in Twelve Books of Verse[a][b]) is an epic poem by the Polish poet, writer, translator and philosopher Adam Mickiewicz. The book, written in Polish alexandrines,[1] was first published by Aleksander Jełowicki on 28 June 1834 in Paris.[2] It is deemed one of the last great epic poems in European literature.[3][4]

Pan Tadeusz, Poland's national epic, is compulsory reading in Polish schools and has been translated into 33 languages.[5] A film version, directed by Andrzej Wajda, was released in 1999. In 2014 Pan Tadeusz was incorporated into Poland's list in the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme.[6]

Content

[edit]

The story takes place over the course of five days in 1811 and two days in 1812, at a time in history when Poland had been divided between the armies of Russia, Prussia, and Austria (see Partitions of Poland) and erased from the political map of Europe, although in 1807 Napoleon had established a satellite Duchy of Warsaw in the Prussian partition which remained in existence until the Congress of Vienna held after Napoleon's defeat.[7]

The place is situated within the Russian partition, in the village of Soplicowo, the country estate of the Soplica clan. Pan Tadeusz recounts the story of two feuding noble families, and the love between Tadeusz Soplica (the title character) of one family, and Zosia of the other. A subplot involves a spontaneous revolt of the local inhabitants against the occupying Russian garrison. Mickiewicz, an exile in Paris and thus beyond the reach of Russian censorship, wrote openly about the occupation.[8]

The Polish national poem begins with the words "O Lithuania"; this largely stems from the fact that the 19th-century concept of nationality had not yet been geopoliticized. The term "Lithuania" used by Mickiewicz refers to a geographical region of Grand Duchy of Lithuania within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[9][10][11][12] The invocation of Pan Tadeusz remains one of the most recognizable pieces of Polish poetry.[13]

Compendium ferculorum, albo Zebranie potraw, the oldest cookbook in Polish, served as an inspiration for Mickiewicz's nostalgic description of "the last Old Polish feast" in Pan Tadeusz.[14] In his account of the fictional banquet in Book 12, the poet included the names of several dishes described in Compendium ferculorum, such as "royal borscht", as well as two of the master chef's secrets: the broth with pearls and a coin, and the three-way fish.[15]

Plot

[edit]A young Polish noble, Tadeusz Soplica, comes back from his education in Vilnius to his family estate in Soplicowo. Tadeusz is an orphan raised by his uncle – Judge Soplica, who is a younger brother of Tadeusz's long lost father, Jacek Soplica. Tadeusz is greeted by the Seneschal (Wojski), a family friend. The Seneschal tells him about the trial between the Judge and Count Horeszko concerning the ownership of a castle which once belonged to Pantler Horeszko – the Count's distant relative, a powerful aristocrat who was killed many years before. The trial is currently conducted by the Chamberlain (Podkomorzy), who is a friend and guest of the Judge. Tadeusz also meets Zosia – a young girl, granddaughter of the Pantler, who lives in the Judge's household, and her caretaker Telimena – the Judge's cousin. Tadeusz takes an interest in Zosia, but also flirts with Telimena.

Meanwhile, Count Horeszko visits the Castle, where he is greeted by Gerwazy, the warden and an old servant of the late Pantler. The Count reveals to Gerwazy he has little interest in the Castle and intends to give up the trial. Gerwazy in response tells the Count the story of the conflict between Soplica's and Horeszko's family. The Pantler often invited Jacek Soplica, Tadeusz's father, to the Castle, as Jacek was very popular amongst lesser nobles in the land. Jacek aspired to marry the Pantler's daughter, but was refused by the Pantler. Later, when Russian troops stormed the Castle during the Kościuszko's uprising, Jacek suddenly arrived on the scene and shot the Pantler. Gerwazy swore to avenge his master, but Jacek disappeared. The story makes the Count excited about the conflict with the Soplicas and he decides he has to take the Castle back from the Judge.

News spreads that a bear was seen in a nearby forest. A great hunt for it begins, in which, amongst others, Tadeusz, the Seneschal, the Count and Gerwazy take part. Tadeusz and the Count are both attacked by the bear. They are saved by Father Robak, a Bernardin monk, who unexpectedly appears, grabs Gerwazy's gun and shoots the bear. After the hunt, the Judge decides to give a feast. His servant Protazy advises to do so in the Castle, to demonstrate to everyone the Judge is its host. During the feast, an argument breaks out when Gerwazy accuses the Judge of trespassing and attacks Protazy when he accuses Gerwazy of the same. The Count stands in defense of Gerwazy and claims the Castle as his own. Fight ensues until Tadeusz stops it by challenging the Count to a duel next day. The Count angrily leaves and orders Gerwazy to get the support of lesser nobility of nearby villages to deal with the Soplicas by force.

Father Robak meets with the Judge and scolds him for the incident at the Castle. He reminds the Judge that his brother, Jacek, wanted him to make peace with the Horeszkos to atone for his murder of the Pantler. For that purpose, Jacek arranged for Zosia to be raised by the Soplicas and intended for her to marry Tadeusz, to bring the two conflicted houses together. Father Robak also speaks about Napoleonic armies soon arriving in Lithuania, urging that Poles should unite to fight against the Russians, rather than fight each other in petty disputes. The Judge is enthusiastic about fighting against the Russians but claims that the Count, being younger, should be the first to apologize.

The impoverished nobles of the land gather on Gerwazy's call. They argue among themselves about organizing an uprising against the Russian forces occupying the land and news about the Napoleonic army, which they heard from Father Robak. Gerwazy convinces them that the Soplicas are the enemy within which should be dealt with first.

The Count soon arrives at the Soplicas' manor and takes the family hostage with the help of his new supporters. However, the next day, Russian troops stationing nearby, intervene and arrest the Count's followers, including Gerwazy. The Russian are commanded by Major Płut, who is actually a Pole who made a career in the Russian army. The second in command is Captain Ryków, a Russian sympathetic to the Poles. The Judge tries to convince Major Płut that the whole matter is just a quarrel between two neighbours and claims that he doesn't bring any complaints against the Count. Płut however considers the Count's supporters to be rebels. The Judge reluctantly accepts the Russians at his house, where, on the advice of Father Robak he gets them drunk, while Robak frees the arrested nobles. The fight breaks out when Major Płut makes drunken advances on Telimena and Tadeusz punches him in her defense. During the battle, Father Robak saves the Count's and Gerwazy's life, getting seriously wounded in the process. Captain Ryków ultimately surrenders the battle after suffering serious losses to the Poles, while Major Płut disappears.

Afterwards, the Judge tries to bribe Ryków to keep the whole incident silent. The Russian refuses the money, but promises the whole thing will be blamed on Major Płut drunkenly giving orders to attack. Gerwazy confesses he killed Płut to keep him silent.

Father Robak predicts he will likely die the following night because of the wounds he suffered. He asks to talk alone with Gerwazy with just his brother, the Judge, present. He reveals he is really Jacek Soplica and tells his side of the story of the Pantler's death. Jacek and the Pantler's daughter were in love. The Pantler was aware of this, but, thinking Jacek of too low birth to marry his daughter, pretended to be oblivious. The Pantler treated Jacek as a friend for political reasons, needing his influence amongst the lesser nobility. Jacek suffered through the charade, until the Pantler openly asked him for an opinion about another candidate for a husband for his daughter. Jacek left without a word, intending to never visit the Castle again. Much later he witnessed the Castle being stormed by the Russians. Seeing the Pantler victorious and proud made Jacek overwhelmed with grief and anger - which drove him to kill the Pantler.

Gerwazy admits that the Pantler wronged Jacek, and gives up his revenge, considering them even after Jacek (as Father Robak) sacrificed himself to save him and the Count's. Gerwazy also reveals that the dying Pantler gave him a sign he forgave his killer. Father Robak dies the following night.[16]

The nobles who took part in the battle against the Russians, including Tadeusz and the Count, are forced to leave the country, as they are in threat of being arrested by the Russian authorities. A year later, they come back as soldiers of the Polish troops in Napoleonic army. Gerwazy and Protazy, now friends, reminisce on the events from a year before. Tadeusz and Zosia get engaged.

Other translations

[edit]There have been multiple English translations:

- 1885 Maude Ashurst Biggs, under the title "Master Thaddeus"

- 1917 George Rapall Noyes, prose translation[17]

- 1962 Watson Kirkconnell, under the title "Sir Thaddeus"

- 1986 Kenneth R. Mackenzie (ISBN 9780781800334)

- 2005 Marcel Weyland, translation in the original meter (ISBN 1567002196 US and ISBN 1873106777 UK)

- 2018 Bill Johnston (ISBN 9781939810007)[18] who received the National Translation Award bestowed by the American Literary Translators Association.[19]

- 2019 Christopher Adam Zakrzewski, prose translation (ISBN 9781945430756)

The earliest translation of Pan Tadeusz was into Belarusian by the Belarusian writer and dramatist Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich, in Vilnius in 1859.[20] Because of the pressure from Tsarist authorities, Dunin-Martshinkyevich was able to publish only the first two chapters of the poem.

Film adaptations

[edit]The first film version of the poem as a feature was produced in 1928. The film version made by Andrzej Wajda in 1999 was his great cinematic success in Poland.

Popular recognition

[edit]In 2012, during the first edition of the National Reading Day organized by the President of Poland Bronisław Komorowski, Pan Tadeusz was read in numerous locations across the country as a way of promoting readership and popularizing Polish literature.[21][22] Google's Doodle for Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Iceland, Ireland and UK on 28 June 2019 commemorated the poem.[23][24]

Gallery

[edit]-

Illustration to Book III of Pan Tadeusz by Adam Mickiewicz. Picking Mushrooms, painting by Franciszek Kostrzewski, ca. 1860.

-

Illustration to Book VII of Pan Tadeusz. Gerwazy showing off his sword called Scyzoryk (Pocketknife), by Michał Andriolli.

-

The Hunt, illustration to Book IV

-

Jankiel's Concert, oil on canvas by Maurycy Trębacz (1861–1941)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Polish original: Pan Tadeusz, czyli ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem. English translations have also used the title Master Thaddeus.

- ^ A foray (zajazd), in this context, was a method of enforcing land rights among the Polish privileged nobility.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Historical House: Pan Tadeusz". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ Literatura polska. Przewodnik encyklopedyczny (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. 1984. ISBN 83-01-05368-2.

- ^ Czesław Miłosz, The history of Polish literature. IV. Romanticism, p. 228. Google Books. University of California Press, 1983. ISBN 0-520-04477-0. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ "Pan Tadeusz Poem: Five things you need to know about this epic Polish masterpiece". Archived from the original on 2022-05-24. Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ "Pan Tadeusz w Google Doodle. Pierwsza publikacja książki obchodzi 185 urodziny". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ ""Pan Tadeusz" na Polskiej Liście UNESCO". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ "A Lithuanian Romeo and Juliet: Pan Tadeusz, by Adam Mickiewicz, reviewed". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ "Pan Tadeusz – Adam Mickiewicz". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ Jonathan Bousfield (2004). Baltic States. Rough Guides. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-85828-840-6.

- ^ Gerard Carruthers; Colin Kidd (2018). Literature and Union: Scottish Texts, British Contexts. Oxford University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-19-873623-3.

- ^ Ton Otto; Poul Pedersen (31 December 2005). Tradition and Agency: Tracing Cultural Continuity and Invention. Aarhus University Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-87-7934-952-0.

- ^ Je̜drzej Giertych; Jędrzej Giertych (1981). In Defence of My Country. J. Giertych.

Mickiewicz begins his greatest work, "Pan Tadeusz", with the words "O Lithuania, my fatherland". Of course, he considers Lithuania to be a province of Poland.

- ^ "Inwokacja - interpretacja, środki stylistyczne, analiza - Pan Tadeusz - Adam Mickiewicz". poezja.org (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ Bąbel, Agnieszka M. (2000a). "Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku" [The pot and the book: relationships between culinary and literary texts in Polish literature of the 19th century] (PDF). Teksty Drugie: Teoria Literatury, Krytyka, Interpretacja (in Polish). 6. Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk: 163–181. ISSN 0867-0633. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- ^ Ocieczek, Renarda (2000). "'Zabytek drogi prawych zwyczajów' – o książce kucharskiej, którą czytywał Mickiewicz" ["The Precious Monument of Righteous Customs" – on the cookery book that Mickiewicz used to read]. In Piechota, Marek (ed.). "Pieśni ogromnych dwanaście...": Studia i szkice o Panu Tadeuszu ["Twelve great cantos...": Studies and essays on Pan Tadeusz] (PDF) (in Polish). Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. pp. 171–191. ISBN 83-226-0598-2. ISSN 0208-6336. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^ "Pan Tadeusz - streszczenie - Adam Mickiewicz". poezja.org (in Polish). Retrieved 2022-11-07.

- ^ "The prose translation of Pan Tadeusz by Noyes".

- ^ "New translation of Pan Tadeusz". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ "Top US award given for translation of Polish epic poem". Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ (in Russian) Лапидус Н. И., Малюкович С. Д. Литература XIX века. М.: Университетское, 1992. P.147

- ^ "Presidential couple launch National Reading event". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ "National Reading Day". Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ Whitfield, Kate (28 June 2019). "Pan Tadeusz Poem: Why is Google paying tribute to the epic Polish masterpiece today?". Daily Express. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "185th Anniversary of the Publication of Pan Tadeusz Poem". 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

External links

[edit] The full text of Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books at Wikisource, translated by George Rapall Noyes, 1917; the text also available from archive.org and Project Gutenburg

The full text of Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books at Wikisource, translated by George Rapall Noyes, 1917; the text also available from archive.org and Project Gutenburg- Pan Tadeusz at Standard Ebooks

- Pan Tadeusz or the Last Foray in Lithuania: a History of the Nobility in the Years 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books of Verse translated by Leonard Kress

- Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry During 1811–1812 translated by Marcel Weyland, 2004

- Adam Mickiewicz. Sinjoro Tadeo, aŭ la lasta armita posedopreno en Litvo. Nobelara historio de la jaroj 1811 kaj 1812 en dekdu libroj verse esperanta.. Pan Tadeusz in Esperanto, translated by Antoni Grabowski