Ilya Kabakov

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Ilya Kabakov | |

|---|---|

| Илья Кабаков | |

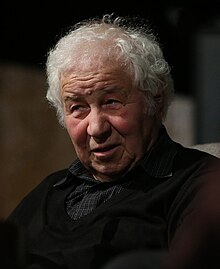

Kabakov in 2017 | |

| Born | Ilya Iosifovich Kabakov September 30, 1933 |

| Died | May 27, 2023 (aged 89) New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Installation art |

| Spouse | Emilia Kanevsky |

Ilya Iosifovich Kabakov (Russian: Илья́ Ио́сифович Кабако́в; September 30, 1933 – May 27, 2023) was a Russian–American conceptual artist, born in Dnipropetrovsk in what was then the Ukrainian SSR of the Soviet Union. He worked for thirty years in Moscow, from the 1950s until the late 1980s. After that he lived and worked on Long Island, United States.[2]

Early life

[edit]Ilya Iosifovich Kabakov was born on September 30, 1933, in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[3] His mother, accountant Bertha Judelevna Solodukhina, and his father, locksmith Iosif Bentcionovitch Kabakov, were Jewish. Ilya was evacuated during World War II to Samarkand with his mother. There he started attending the school of the Leningrad Academy of Art which was evacuated to Samarkand. His classmates included the painter Mikhail Turovsky.

Education

[edit]After World War II his family moved to Moscow. From 1945 to 1951, he studied at the Moscow Art School; in 1957 he graduated from V.I. Surikov State Art Institute, Moscow, where he specialized in graphic design and book illustration.

Career

[edit]This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (May 2023) |

Unlike many underground Soviet artists, Kabakov joined the Union of Soviet Artists in 1959 and became a full member in 1962. This was a prestigious position in the USSR and it brought with it substantial material benefits. In general, Kabakov illustrated children's books for 3 to 6 months a year and then spent the remainder of his time on his own projects.

In the vibrant art scene of 1970s Moscow, Ilya Kabakov's unconventional talent found an unexpected champion in Dina Vierny, a distinguished gallerist with a keen eye for groundbreaking art. Vierny, after a visit in Moscow in the early 1970’s, committed to supporting artists resisting the constraints of socialist realism, discovered Kabakov. The fateful meeting occurred on the evening of January 16, 1970, when Vierny recognized Kabakov as an artist of exceptional originality, despite being unknown and prohibited from exhibiting in Moscow. Vierny's genuine interest in Kabakov's work transcended time, enduring for over 27 years. Despite Kabakov's infrequent exhibitions in Moscow, his drawings managed to captivate international audiences. Vierny not only encouraged Kabakov to leave the Soviet Union for broader recognition but also actively supported him by acquiring a substantial number of his works. This support was not limited to Kabakov alone; Vierny, upon her return, brought back works by other non-conformist artists such as Erik Boulatov and Vladimir Yankilevsky, known as the Group of Boulevard Sretensky. Together, these artists, despite differing styles, shared a common struggle against state-imposed artistic limitations, particularly the constraints of socialist realism. Vierny's commitment culminated in the groundbreaking exhibition "Russian Avant-Garde - Moscow 1973" at her Saint-Germain-des-Prés gallery, showcasing the diverse yet united front of non-conformist artists challenging the artistic norms of their time.

The 1980s

[edit]Between 1983 and 2000, Kabakov created 155 installations.[citation needed] Of these, one of the best known installations is The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment. First created in 1985 in a secret attic studio in Moscow, Kabakov later recreated the piece in the United States at Ronald Feldman Gallery in 1988. The installation portrays a small, run-down bedroom with a large hole in the ceiling and propaganda photos covering the walls.[2] The exhibition was widely reviewed, securing Kabakov's reputation in the New York art world. [4]

Personal life and death

[edit]In 1989, Kabakov began working with his niece, [5][6] curator and dealer Emilia Kanevsky, who would later become his wife[5] and who emigrated from the USSR in 1973.[7] Kabakov had met her when she lived in Dnipropetrovsk. [5][8] For three decades, the couple collaborated on numerous exhibitions, including Documenta in 1992, the Venice Biennale in 1993, the Whitney Biennial in 1997, the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg in 2004, and the Tate Modern and the Hirshhorn in 2017.[2]

Kabakov died on May 27, 2023, at the age of 89.[9][10]

Exhibitions and collectors

[edit]Following Mikhail Chemiakin's 1995 show, Ilya Kabakov had one of the first major solo exhibitions of a living Russian artist at the new State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg in 2004.

His works are included in the collections of the Zimmerli Art Museum, the Centre Pompidou (Beaubourg), Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim, The Hermitage, Tretjakov Gallery (Moscow), Norway Museum Of Contemporary Art, the Kolodzei Art Foundation and museums in Columbus, Ohio, Frankfurt, and Köln, etc.

In 2017 the Tate Modern in London exhibited Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. set up an exhibition Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Utopian Projects.

National Museum of Norway (Norway) has "Søppelmannen" ['the garbage man'] on permanent display.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Siebold-Bultman, Ursula (2000). Birksted, Jan (ed.). New projects for the City of Munster: Ilya Kabakov, Herman de Vries and Dan Graham (1st ed.). London & New York: Spon Pres, Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 205–222. ISBN 0419250700.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Ilya Kabakov, the Ukrainian American Conceptual Artist Who Lived Through Totalitarianism but Dreamed of Utopia, Has Died at 89". May 30, 2023.

- ^ "'The real departure will occur on its own, in its own time': Pioneering artist Ilya Kabakov has died, aged 89". May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Remembering Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment - Notes - e-flux".

- ^ a b c "Концептуальные жуки, советский быт и бегство от реальности Ильи Кабакова". Bird In Flight. July 7, 2017.

- ^ "Илья Кабаков". 24SMI.

- ^ "Выставка Кабаковых | Журнал "ПРОСТО"". Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Илья Кабаков". 24SMI.

- ^ Умер российский художник Кабаков. Tass.ru. May 28, 2023

- ^ "Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023)". Artforum. May 30, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Karin Hellandsjø. "Bindeleddet mellom fortid og framtid". Klassekampen. 2023-06-12. P. 25

Further reading

[edit]- Alexander Rappaport. The Ropes of Ilya Kabakov: An Experiment in Interpretation of a Conceptual Installation // Tekstura: Russian essays on visual culture / Ed. and translated by A. Efimova and L. Manovich. University of Chicago Press, 1993. — ISBN 0-226-95123-5, ISBN 978-0-226-95123-2

- Stoos, Toni, ed. Ilya Kabakov Installations: 1983–2000 Catalogue Raisonne Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2003, 2 volumes.

- Kabakov, Ilya. 5 Albums, Helsinki: The Museum of Contemporary Art and the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo. Helsinki: ARTPRINT, 1994. ISBN 951-47-8835-4

- Martin, Jean-Hubert and Claudia Jolles. Ilya Kabakov: Okna, Das Fenster, The Window, Bern: Benteli Verlag, 1985.

- 1973 Avant-Garde russe exitibition catalogue

- Wallach, Amei. Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away, New York: Harry Abrams, 1996.

- Meyer, Werner, ed. Ilya Kabakov: A Universal System for Depicting Everything Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2002.

- Groys, Boris, David A. Ross, Iwona Blaznick. Ilya Kabakov, London: Phaidon, 1998. ISBN 0-7148-3797-0

- Rattemeyer, Volker, ed. Ilya Kabakov: Der rote Waggon, Nurnberg: verlag fur modern kunst, 1999. ISBN 3-933096-25-1

- Kabakov, Ilya. The Communal Kitchen, Paris: Musee Maillol, 1994.

- Kabakov, Ilya. 10 Characters, New York: Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, 1988.

- Osaka, Eriko ed., Ilya Kabakov. Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal (1898–1933), Contemporary Art Center: Art Tower Mito, Japan, 1999, 2 volumes.

- Kabakov, Ilya. Ilya Kabakov on Ulo Sooster's Paintings: Subjective Notes, Tallinn: "Kunst" publishing house, 1996.

- Kabakov, Ilya and Vladimir Tarasov. Red Pavilion, Venice Biennale Venice: Venice Biennale, 1993.

- Kabakov, Ilya. Life of Flies, Koln: Edition Cantz, 1992.

- Kabakov et al. Ilya Kabakov: Public Projects or the Spirit of a Place, Milan: Charta, 2001, ISBN 88-8158-302-X.

- Groys, Boris (2006). Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment. The MIT Press. ISBN 1-84638-004-9.

- Jackson, Matthew Jesse. The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-226-38941-7

- Ilya Kabakov; Kabakov's Installations

External links

[edit]- Official website

- https://galeriedinavierny.fr/artistes/ilya-kabakov/

- https://www.connaissancedesarts.com/depeches-art/deces/mort-de-lartiste-conceptuel-ilya-kabakov-deboulonneur-dutopies-11182703/

- Emilia and Ilya Kabakov at ARNDT Berlin

- Thaddaeus Ropac

- Edelman Arts Archived December 28, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Sloane Gallery of Art Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Ilya Kabakov in the Soviet era

- "Kabakov o el amor por el gran teatro del individuo", Revista Distopía

- Ilya Kabakov at IMDb

- Ilya Kabakov discography at Discogs

- 1933 births

- 2023 deaths

- Soviet Nonconformist Art

- Soviet painters

- American installation artists

- Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Arts

- Soviet people of Jewish descent

- Artists from Dnipro

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale

- Russian contemporary artists