Iphigenia in Tauris

| Iphigenia in Tauris | |

|---|---|

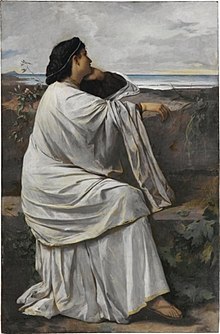

Iphigenie (1871) by Anselm Feuerbach | |

| Written by | Euripides |

| Chorus | Greek Slave Women |

| Characters | Iphigenia Orestes Pylades King Thoas Athena herdsman servant |

| Place premiered | Athens |

| Original language | Ancient Greek |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Setting | Taurica, a region of Scythia in the northern Black Sea |

Iphigenia in Tauris (Ancient Greek: Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Ταύροις, Iphigeneia en Taurois) is a drama by the playwright Euripides, written between 414 BC and 412 BC. It has much in common with another of Euripides's plays, Helen, as well as the lost play Andromeda, and is often described as a romance, a melodrama, a tragi-comedy or an escape play.[1][2]

Although the play is generally known in English as Iphigenia in Tauris, this is, strictly speaking, the Latin title of the play (corresponding to the Greek Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Ταύροις), the meaning of which is Iphigenia among the Taurians. There is no such place as "Tauris" in Euripides' play, although Goethe, in his play Iphigenie auf Tauris ironically utilising this translation error, posits such a place.[3] The name refers to the Crimean Peninsula (ancient Taurikḗ).

Background

[edit]Years before the time period covered by the play, the young princess Iphigenia narrowly avoided death by sacrifice at the hands of her father, Agamemnon. (See plot of Iphigenia at Aulis.) At the last moment the goddess Artemis, to whom the sacrifice was to be made, intervened and replaced Iphigenia on the altar with a deer, saving the girl and sweeping her off to the land of the Taurians. She has since been made a priestess at the temple of Artemis in Taurica, a position in which she has the gruesome task of ritually sacrificing foreigners who land on King Thoas's shores.

Iphigenia hates her forced religious servitude and is desperate to contact her family in Greece. She wants to inform them that, thanks to the miraculous swap performed by Artemis, she is still alive and wants to return to her homeland, leaving the role of high priestess to someone else. Furthermore, she has had a prophetic dream about her younger brother Orestes and believes that he is dead.

Meanwhile, Orestes has killed his mother Clytemnestra to avenge his father Agamemnon with assistance from his friend Pylades. He becomes haunted by the Erinyes for committing the crime and goes through periodic fits of madness. He is told by Apollo to go to Athens to be brought to trial (as portrayed in Eumenides by Aeschylus). Although the trial ends in his favour, the Erinyes continue to haunt him. Apollo sends him to steal a sacred statue of Artemis to bring back to Athens so that he may be set free.

Plot

[edit]The scene represents the front of the temple of Artemis in the land of the Taurians (presently, the Crimean peninsula). The altar is in the center.

The play begins with Iphigenia reflecting on her brother's death. She recounts her "sacrifice" at the hands of Agamemnon, and how she was saved by Artemis and made priestess in this temple. She has had a dream in which the structure of her family's house crashed down in ruins, leaving only a single column which she then washed clean as if preparing it for ritual sacrifice. She interprets this dream to mean that Orestes is dead.

Orestes and Pylades enter, having just arrived in this land. Orestes was sent by Apollo to retrieve the image of Artemis from the temple, and Pylades has accompanied him. Orestes explains that he has avenged Agamemnon's death by killing Clytaemnestra and Aegisthus. The two decide to hide and make a plan to retrieve the idol without being captured. They know that the Taurians sacrifice Hellene blood in their temple of Artemis. Orestes and Pylades exit. Iphigenia enters and discusses her sad life with the chorus, composed of captive Greek maidens, attendants of Iphigenia. She believes that her father's bloodline has ended with the death of Orestes.

A herdsman enters and explains to Iphigenia that he has captured two Hellenes and that Iphigenia should make ready the lustral water and the rites of consecration. The herdsman heard one called Pylades by the other, but did not hear the name of the other. Iphigenia tells the herdsmen to bring the strangers to the temple, and says that she will prepare to sacrifice them. The herdsman leaves to fetch the strangers. Iphigenia explains that she was tricked into going to Aulis, through the treachery of Odysseus. She was told that she was being married to Achilles, but upon arriving in Aulis, she discovered that she was going to be sacrificed by Agamemnon. Now, she presides over the sacrifices of any Hellene trespassers in the land of the Taurians, to avenge the crimes against her.

Orestes and Pylades enter in bonds. Iphigenia demands that the prisoners' bonds be loosened, because they are hallowed. The attendants to Iphigenia leave to prepare for the sacrifice. Iphigenia asks Orestes his origins, but Orestes refuses to tell Iphigenia his name. Iphigenia finds out which of the two is Pylades and that they are from Argos. Iphigenia asks Orestes many questions, especially of Greeks who fought in Troy. She asks if Helen has returned home to the house of Menelaus, and of the fates of Calchas, Odysseus, Achilles, and Agamemnon. Orestes informs Iphigenia that Agamemnon is dead, but that his son lives. Upon hearing this, Iphigenia decides that she wants one of the strangers to return a letter to Argos, and that she will only sacrifice one of them. Orestes demands that he be sacrificed, and that Pylades be sent home with the letter, because Orestes brought Pylades on this trip, and it would not be right for Pylades to die while Orestes lives.

Pylades promises to deliver the letter unless his boat is shipwrecked and the letter is lost. Iphigenia then recites the letter to Pylades so that, if it is lost, he can still relay the message. She recites:

She that was sacrificed in Aulis send this message, Iphigenia, still alive, though dead to those at Argos. Fetch me back to Argos, my brother, before I die. Rescue me from this barbarian land, free me from this slaughterous priesthood, in which it is my office to kill strangers. Else I shall become a curse upon your house, Orestes. Goddess Artemis saved me and substituted a deer, which my father sacrificed believing he was thrusting the sharp blade into me. Then she brought me to stay in this land.[4]

During this recitation, Orestes asks Pylades what he should do, having realized that he was standing in front of his sister.

Orestes reveals his identity to Iphigenia, who demands proof. First, Orestes recounts how Iphigenia embroidered the scene of the quarrel between Atreus and Thyestes on a fine web. Orestes also spoke of Pelops’ ancient spear, which he brandished in his hands when he killed Oenomaus and won Hippodamia, the maid of Pisa, which was hidden away in Iphigenia's maiden chamber. This is evidence enough for Iphigenia, who embraces Orestes. Orestes explains that he has come to this land by the bidding of Phoebus's oracle, and that if he is successful, he might finally be free of the haunting Erinyes.

Orestes, Pylades, and Iphigenia plan an escape whereby Iphigenia will claim that the strangers need to be cleansed in order to be sacrificed and will take them to the bay where their ship is anchored. Additionally, Iphigenia will bring the statue that Orestes was sent to retrieve. Orestes and Pylades exit into the temple. Thoas, king of the Taurians, enters and asks whether or not the first rites have been performed over the strangers. Iphigenia has just retrieved the statue from the temple and explains that when the strangers were brought in front of the statue, the statue turned and closed its eyes. Iphigenia interprets it thus to Thoas: The strangers arrived with the blood of kin on their hands and they must be cleansed. Also, the statue must be cleansed. Iphigenia explains that she would like to clean the strangers and the statue in the sea, to make for a purer sacrifice. Thoas agrees that this must be done, and suspects nothing. Iphigenia tells Thoas that he must remain at the temple and cleanse the hall with torches, and that she may take a long time. All three exit the stage.

A messenger enters, shouting that the strangers have escaped. Thoas enters from the temple, asking what all the noise is about. The messenger explains Iphigenia's lies and that the strangers fought some of the natives, then escaped on their Hellene ship with the priestess and the statue. Thoas calls upon the citizens of his land to run along the shore and catch the ship. Athena enters and explains to Thoas that he shouldn't be angry. She addresses Iphigenia, telling her to be priestess at the sacred terraces of Brauron, and she tells Orestes that she is saving him again. Thoas heeds Athena's words, because whoever hears the words of the gods and heeds them not is out of his mind.

Date

[edit]

The exact date of Iphigenia in Tauris is unknown. Metrical analysis by Zielinski indicated a date between 414 and 413 BCE, but later analysis by Martin Cropp and Gordon Fick using more sophisticated statistical techniques indicated a wider range of 416 to 412 BCE.[5] The plot of Iphigenia in Tauris is similar to that of Euripides' Helen and Andromeda, both of which are known to have been first performed in 412. This has often been taken as a reason to reject 412 as the date for Iphigenia in Tauris, since that would mean three similar plays would have been performed in the same trilogy. However, Matthew Wright believes the plot and other stylistic similarities between the three plays indicates that they most likely were produced as part of the same trilogy in 412.[5] Among Wright's reasons are the fact that although the plots are similar they are not identical, and that this type of escape plot may have been particularly relevant in 412 at the first Dionysia after Athens' failed Sicilian Expedition.[5] Also, other than this play and the two plays known to date to 412, we do not know of any such escape plays by Euripides; if he produced two that year, why not three, which might make a particularly strong impression if the escape theme was one Euripides wished to emphasize that year.[5] Finally, Aristophanes overtly parodied Helen and Andromeda in his comedy Thesmophoriazusae, produced in 411, and Wright sees a more subtle parody of Iphigenia in Tauris in the final escape plan attempted in Thesmophoriazusae as well.[5]

Translations

[edit]- Robert Potter, 1781 – verse: full text

- Edward P. Coleridge, 1891 – prose

- Gilbert Murray, 1910 – verse: full text

- Arthur S. Way, 1912 – verse

- Augustus T. Murray, 1931 – prose

- Moses Hadas and John McLean, 1936 - prose [6]

- Robert Potter, 1938 – prose: full text

- Witter Bynner, 1956 – verse

- Richmond Lattimore, 1973

- Philip Vellacott, 1974 – prose and verse

- David Kovacs, 1999 – prose

- J. Davie, 2002

- James Morwood, 2002

- George Theodoridis, 2009 – prose: full text

- Anne Carson, 2014

- Brian Vinero, 2014: verse[7]

Later works inspired by the play

[edit]

Painting

[edit]Wall painting at House of the Citharist, Pompeii (pre-79 AD.)[8]

Sculpture

[edit]Roman relief carving around stone column discovered in Fittleworth, West Sussex (1st century AD.)[9]

Plays

[edit]- Charition mime (2nd century) is possibly a parody of Iphigenia in Tauris. Like Iphigenia, Charition is kept captive at a temple in a distant land (India). Her brother and a clown arrive in India, and rescue her by tricking the local king.[10]

- Guimond de la Touche, Iphigénie en Tauride (1757)

- Goethe, Iphigenie auf Tauris (1787)

- Jeff Ho (Ho Ka Kei) (Canadian Playwright), "Iphigenia and the Furies (On Taurian Land)." (Produced 2019, Published 2022)[11]

Operas

[edit]- André Campra and Henri Desmarets, Iphigénie en Tauride (1704)

- George Frideric Handel, Oreste (1734)

- José de Nebra, Para obsequio a la deydad, nunca es culto la crueldad. Iphigenia en Tracia (1747)

- Tommaso Traetta, Ifigenia in Tauride (1763)

- Gluck, Iphigénie en Tauride (1779), the most famous operatic version of the story

- Niccolò Piccinni, Iphigénie en Tauride (1781)

References

[edit]- ^ Wright, M. (2005). Euripides' Escape-Tragedies: A Study of Helen, Andromeda, and Iphigenia among the Taurians. Oxford University Press. pp. 7–14. ISBN 978-0-19-927451-2.

- ^ Kitto, H.D.F. (1966). Greek Tragedy. Routledge. pp. 311–329. ISBN 0-415-05896-1.

- ^ Parker, L.P.E. (2016) Iphigenia in Tauris. Oxford. p. lxxii n. 143. See, moreover, the review of Parker's edition by M. Lloyd, in Acta Classica 59 (2016) p. 228.

- ^ Euripides. Iphigenia Among the Taurians. Trans. Moses Hadas and John McLean. New York: Bantam Dell, 2006. Print. Pages 294-295.

- ^ a b c d e Wright, M. (2005). Euripides' Escape-Tragedies: A Study of Helen, Andromeda, and Iphigenia among the Taurians. Oxford University Press. pp. 43–51. ISBN 978-0-19-927451-2.

- ^ Moses Hadas and John McLean (trans.), Ten Plays by Euripides (New York: Dial Press, 1936).

- ^ "Iphigenia at Tauris". pwcenter.org. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 2022-10-28.

- ^ Black, E.; Edgar, J.; Hayward, K.M.J.; Henig, M. (2012). "A New Sculpture of Iphigenia in Tauris". Britannia. 43: 243–249. doi:10.1017/S0068113X12000244.

- ^ "Britannia 2012 – Iphigenia | Jon Edgar".

- ^ Jack Lindsay (1963). Daily Life in Roman Egypt. F. Muller. p. 183.

- ^ Playwrights Canada Press https://www.playwrightscanada.com/Books/I/Iphigenia-and-the-Furies-On-Taurian-Land-Antigone

External links

[edit] Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Ταύροις

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Ταύροις Iphigenia in Tauris public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Iphigenia in Tauris public domain audiobook at LibriVox