Wisdom tooth

| Wisdom tooth | |

|---|---|

Wisdom teeth in the human mouth for permanent teeth. There are none in deciduous (children's) teeth. | |

Wisdom teeth | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D008964 |

| TA98 | A05.1.03.008 |

| TA2 | 911 |

| FMA | 321612 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

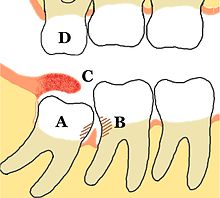

The third molar, commonly called wisdom tooth, is the most posterior of the three molars in each quadrant of the human dentition. The age at which wisdom teeth come through (erupt) is variable,[1] but this generally occurs between late teens and early twenties.[2] Most adults have four wisdom teeth, one in each of the four quadrants, but it is possible to have none, fewer, or more, in which case the extras are called supernumerary teeth. Wisdom teeth may become stuck (impacted)[3] and not erupt fully, if there is not enough space for them to come through normally. Impacted wisdom teeth are still sometimes removed for orthodontic treatment, believing that they move the other teeth and cause crowding, though this is no longer held as true.[4][5]

Impacted wisdom teeth may suffer from tooth decay if oral hygiene becomes more difficult. Wisdom teeth which are partially erupted through the gum may also cause inflammation[3] and infection in the surrounding gum tissues, termed pericoronitis. More conservative treatments, such as operculectomies, may be appropriate for some cases. However, impacted wisdom teeth are commonly extracted to treat or prevent these problems. Some sources oppose the prophylactic removal of disease-free impacted wisdom teeth, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK.[4][6][7]

History

[edit]Although formally known as third molars, the common name is wisdom teeth because they appear so late – much later than the other teeth, at an age where people are presumably "wiser" than as a child, when the other teeth erupt.[8] The term probably came as a translation of the Latin dens sapientiae. Their eruption has been known to cause dental issues for millennia; it was noted at least as far back as Aristotle:

The last teeth to come in man are molars called 'wisdom-teeth', which come at the age of twenty years, in the case of both sexes. Cases have been known in women upwards of eighty years old where at the very close of life the wisdom-teeth have come up, causing great pain in their coming; and cases have been known of the like phenomenon in men too. This happens, when it does happen, in the case of people where the wisdom-teeth have not come up in early years.

— Aristotle, The History of Animals[9]

The oldest known impacted wisdom tooth belonged to a European woman who lived between 13,000 and 11,000 BCE, in the Magdalenian period.[10] Nonetheless, molar impaction was relatively rare prior to the modern era. With the Industrial Revolution, the affliction became ten times more common, owing to the new prevalence of soft, processed foods.[11][12]

Structure

[edit]

Tooth morphology

[edit]Morphology of wisdom teeth can be variable.

Maxillary (upper) third molars commonly have a triangular crown with a deep central fossa from which multiple irregular fissures originate. Their roots are commonly fused together and can be irregular in shape.

Mandibular (lower) third molars are the smallest molar teeth in the permanent dentition. The crown usually takes on a rounded rectangular shape that features four or five cusps with an irregular fissure pattern. Roots are greatly reduced in size and can be fused together.[13]

Dental notation

[edit]There are several notation systems used in dentistry to identify teeth. Under the Palmer/Zsigmondy system, the right and left maxillary wisdom teeth are represented by 8⏌ and ⎿8, while 8⏋ and ⎾8 represent the right and left mandibular wisdom teeth.[14] Under the FDI notational system, the right and left maxillary third molars are numbered 18 and 28, respectively, and the right and left mandibular third molars are numbered 48 and 38.[15] According to the Universal Numbering System the right and left upper wisdom teeth are numbered 1 and 16 and the right and left lower wisdom teeth are 17 and 32.[16]

Variation

[edit]Agenesis of wisdom teeth differs by population, ranging from practically zero in Aboriginal Tasmanians to nearly 100% in indigenous Mexicans.[17][18] The difference is related to the PAX9 and MSX1 genes (and perhaps other genes).[19][20][21][22]

Age of eruption

[edit]There is significant variation between the reported age of eruption of wisdom teeth between different populations.[23] For example, wisdom teeth tend to erupt earlier in people with African heritage compared to people of Asian and European heritage.[23]

Generally wisdom teeth erupt most commonly between age 17 and 21.[1] Eruption may start as early as age 13 in some groups[23] and typically occurs before the age of 25.[24] If they have not erupted by age 25, oral surgeons generally consider that the tooth will not erupt spontaneously.[2]

Root development can continue for up to three years after eruption occurs.[25]

Function

[edit]Anthropologists believe human and primate[12] wisdom teeth may help with chewing tougher foods.[26][27] After the advent of agriculture over 10,000 years ago, and especially with the industrial revolution in recent centuries, soft human diets became more common through the use of tools (cutting the food) and cooking to make food easier to chew. Compared to hunter-gatherer populations, post-industrial agriculturalist populations are thought to encounter less masticatory stress and consequently have shorter and thicker mandibles, predisposing them to dental crowding and malocclusion.[28]

Clinical significance

[edit]

Wisdom teeth (often notated clinically as M3 for third molar) have long been identified as a source of problems and continue to be the most commonly impacted teeth in the human mouth. Impaction of the wisdom teeth results in a risk of periodontal disease and dental cavities.[29] Impacted wisdom teeth lead to pathology in 12% of cases.[30]

Impacted wisdom teeth are classified by the direction and depth of impaction, the amount of available space for tooth eruption and the amount of soft tissue or bone that covers them. The classification structure allows clinicians to estimate the probabilities of impaction, infections and complications associated with wisdom teeth removal.[31] Wisdom teeth are also classified by the presence of symptoms and disease.[32]

Treatment of an erupted wisdom tooth is the same as any other tooth in the mouth. If impacted and having a pathology, such as caries or pericoronitis, treatment can be dental restoration for cavities and for pericoronitis, salt water rinses, local treatment to the infected tissue overlying the impaction,[33]: 440–441 oral antibiotics, surgical removal of excess gum flap (operculectomy), or if those failed, extraction or coronectomy.

The National Health Service in the UK recommends people go to dental check-ups every 3–24 months, depending on the state of the teeth and gums and the recommendation of the dentist.[34]

Common pathologies associated with wisdom teeth

[edit]Odontogenic infections are a dental complication originating inside the tooth or in close proximity to the surrounding tissues. There are different types of odontogenic infections which may affect impacted wisdom teeth such as periodontitis, pulpitis, dental abscess and pericoronitis.

Pericoronitis is a common pathology of impacted third molar.[35] It is an acute localized infection of the tissue surrounding the impacted wisdom teeth. Clinically the tissue appears to be red, tender to touch and edematous. The common symptoms the patient’s report are pain ‘that ranges from dull to throbbing to intense’ and often radiates to mouth, ear or floor of the mouth. Moreover, swelling of the cheek, halitosis and trismus can occur.[36]

Odontogenic cysts

[edit]Odontogenic cysts are a less common pathology of the impacted wisdom tooth with some estimates of prevalence from 0.64% to 2.24% of impacted wisdom teeth.[37][38] They are described as ‘cavities filled with liquid, semiliquid or gaseous content with odontogenic epithelial lining and connective tissue on the outside’. However, studies have found cysts to be prevalent in a small percentage of impacted wisdom teeth that are extracted. The most common types associated with impacted third molars are radicular cysts, dentigerous cysts and odontogenic keratocysts.[39] Large cysts take 2–13 years to develop.[38]

Oral hygiene care

[edit]Practice and maintenance of good oral hygiene can help prevent and control some wisdom tooth pathologies. In addition to twice daily toothbrushing, interdental cleaning is recommended to ensure plaque build doesn’t occur in interdental areas. There are various products available for this – dental floss and interdental brushes being the most common.

Removal of impacted wisdom teeth

[edit]Removal of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth with the absence of disease and no evidence of local infection as a prophylactic method has been disputed within the dental community for a long time. There is insufficient reliable scientific evidence for dental health professionals and policy makers to determine if asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth should be removed. Therefore, the decision will depend on a combination of clinical expertise and patient preference. If the tooth is retained, regular check-ups to identify any problems that may occur is recommended. Considering the lack of quality evidence at present, more long-term studies need to be undertaken to obtain a reliable scientific conclusion.[40]

Mandibular third molar surgery recovery

[edit]Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) is a postoperative method used to heal the alveolar socket following the removal of the mandibular third molar. PRF is a second generation result of the isolation of platelets, white blood cells, stem cells and growth factors from blood samples. Studies have shown that when used there are improvements in pain sensations, swelling and a decreased risk of developing dry socket. This method was shown to only reduce symptoms and is not completely preventive. To date there is no clear correlation between the use of PRF after a mandibular third molar removal surgery and the recovery of jaw spasms, bone restoration and soft tissue healing. Further studies with larger study samples are needed to validate current theories.[41]

Prognosis

[edit]About a third of symptomatic unerupted wisdom teeth have been shown to partially erupt and be non-functional or non-hygienic. Studies have also shown that 30% to 60% of people with previously asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth will have an extraction of at least one of them in 4 to 12 years from diagnosis.[42]

Risk factors of inferior alveolar nerve damage

[edit]Temporary and permanent inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) damage is a known complication of the surgical removal of impacted lower third molars, happening in 1 in 85 patients and 1 in 300 extractions, respectively. Studies have shown that certain risk factors may increase the likelihood of IAN damage. Proximity of the impacted third molar root to the mandibular canal, which can be seen in radiographs, has been shown to be a high-risk factor for IAN damage. Alongside this, the depth of impaction of the tooth, surgical technique and surgeons experience are all contributing risk factors for IAN damage during this procedure. Careful case-by-case consideration is crucial to avoid this risk.[43]

Lower anterior teeth crowding

[edit]Lower anterior teeth crowding has been a common discussion among the orthodontic community for decades. In the 1970s it was thought that unerupted wisdom teeth produced a forward directed force which would cause crowding of the anterior segment. Recent research has shown that there is no agreed opinion and that the cause is due to a variety of factors. This includes dental factors such as tooth crown size and primary tooth loss. Skeletal factors which include growth of the maxilla and mandible and the presence of malocclusions. General factors, including the age and gender of the patient. Overall, recent research has suggested that wisdom teeth alone do not cause crowding of teeth.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b McCoy JM (September 2012). "Complications of retention: pathology associated with retained third molars". Atlas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 20 (2): 177–195. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.06.002. ISBN 978-1455747887. PMID 23021395.

- ^ a b Swift JQ, Nelson WJ (September 2012). "The nature of third molars: are third molars different than other teeth?". Atlas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 20 (2): 159–162. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.07.003. PMID 23021392.

- ^ a b "Wisdom Teeth And Orthodontic Treatment: Should I be worried?". Orthodontics Australia. 2020-01-25. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- ^ a b Friedman JW (September 2007). "The prophylactic extraction of third molars: a public health hazard". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (9): 1554–1559. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.100271. PMC 1963310. PMID 17666691.

- ^ Lyros, Ioannis; Vasoglou, Georgios; Lykogeorgos, Theodoros; Tsolakis, Ioannis A.; Maroulakos, Michael P.; Fora, Eleni; Tsolakis, Apostolos I. (May 2023). "The Effect of Third Molars on the Mandibular Anterior Crowding Relapse—A Systematic Review". Dentistry Journal. 11 (5): 131. doi:10.3390/dj11050131. ISSN 2304-6767. PMC 10217727. PMID 37232782.

- ^ "1 Guidance | Guidance on the Extraction of Wisdom Teeth | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 27 March 2000. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "Opposition to Prophylactic Removal of Third Molars (Wisdom Teeth)". www.apha.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ "Wisdom tooth". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2.

- ^ Aristotle (2015). The History of Animals. Translated by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson. Aeterna Press. p. 49.

- ^ "Magdalenian Girl is a woman and therefore has oldest recorded case of impacted wisdom teeth" (Press release). Field Museum of Natural History. March 7, 2006. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ "What teeth reveal about the lives of modern humans". Ohio State News. The Ohio State University. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- ^ a b Boughner J (9 November 2018). "Bad molars? The origins of wisdom teeth". The Conversation. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ Berkovitz BK, Holland GR, Moxham BJ (2017). Oral Anatomy, Histology and Embryology (fifth ed.). Elsevier. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Edward F. Harris (2005). "Tooth-Coding Systems in the Clinical Dental Setting" (PDF). Dental Anthropology. 18 (2): 44. ISSN 1096-9411. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-06.

- ^ ISO (International Organization for Standardization). "ISO 3950:2016". ISO 3950:2016 Dentistry — Designation system for teeth and areas of the oral cavity. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ American Dental Association (August 2022). "Universal Tooth Designation System" (PDF). ValueSet - Universal Tooth Designation System ada.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Rozkovcová E, Marková M, Dolejsí J (1999). "Studies on agenesis of third molars amongst populations of different origin". Sbornik Lekarsky. 100 (2): 71–84. PMID 11220165.

- ^ Sujon, Mamun Khan; Alam, Mohammad Khursheed; Rahman, Shaifulizan Abdul (31 August 2016). "Prevalence of Third Molar Agenesis: Associated Dental Anomalies in Non-Syndromic 5923 Patients". PLoS ONE. 11 (8).

- ^ Pereira TV, Salzano FM, Mostowska A, Trzeciak WH, Ruiz-Linares A, Chies JA, et al. (April 2006). "Natural selection and molecular evolution in primate PAX9 gene, a major determinant of tooth development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (15): 5676–5681. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.5676P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509562103. JSTOR 30050159. PMC 1458632. PMID 16585527.

- ^ Bonczek O, Balcar VJ, Šerý O (November 2017). "PAX9 gene mutations and tooth agenesis: A review". Clinical Genetics. 92 (5): 467–476. doi:10.1111/cge.12986. PMID 28155232. S2CID 29589974.

- ^ Lidral AC, Reising BC (April 2002). "The role of MSX1 in human tooth agenesis". Journal of Dental Research. 81 (4): 274–278. doi:10.1177/154405910208100410. PMC 2731714. PMID 12097313.

- ^ Tallón-Walton V, Manzanares-Céspedes MC, Carvalho-Lobato P, Valdivia-Gandur I, Arte S, Nieminen P (May 2014). "Exclusion of PAX9 and MSX1 mutation in six families affected by tooth agenesis. A genetic study and literature review". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 19 (3): e248–e254. doi:10.4317/medoral.19173. PMC 4048113. PMID 24316698.

- ^ a b c Tsokos M (2008). Forensic Pathology Reviews 5. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 281. ISBN 9781597451109.

- ^ "Wisdom Teeth". American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

They come in between the ages of 17 and 25, a time of life that has been called the "Age of Wisdom."

- ^ Kaveri GS, Prakash S (June 2012). "Third molars: a threat to periodontal health??". Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. 11 (2): 220–223. doi:10.1007/s12663-011-0286-x. PMC 3386422. PMID 23730073.

- ^ Cooper R (February 5, 2007). "Why Do We Have Wisdom Teeth?". Scienceline.org. Archived from the original on 2016-05-03.

- ^ "A grassy trend in human ancestors' diets". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ von Cramon-Taubadel N (December 2011). "Global human mandibular variation reflects differences in agricultural and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (49): 19546–19551. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10819546V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113050108. PMC 3241821. PMID 22106280.

- ^ "Dental cavities: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ Stanley HR, Alattar M, Collett WK, Stringfellow HR, Spiegel EH (March 1988). "Pathological sequelae of "neglected" impacted third molars". Journal of Oral Pathology. 17 (3): 113–117. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1988.tb01896.x. PMID 3135372.

- ^ Juodzbalys G, Daugela P (July 2013). "Mandibular third molar impaction: review of literature and a proposal of a classification". Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Research. 4 (2): e1. doi:10.5037/jomr.2013.4201. PMC 3886113. PMID 24422029.

- ^ Dodson TB (September 2012). "The management of the asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom tooth: removal versus retention". Atlas of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 20 (2): 169–176. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.06.005. PMID 23021394.

- ^ Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA (2012). Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7.

- ^ "Dental check-ups". nhs.uk. 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ López-Píriz R, Aguilar L, Giménez MJ (March 2007). "Management of odontogenic infection of pulpal and periodontal origin". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 12 (2): E154–E159. PMID 17322806.

- ^ López-Píriz R, Aguilar L, Giménez MJ (March 2007). "Management of odontogenic infection of pulpal and periodontal origin". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 12 (2): E154–E159. PMID 17322806.

- ^ Shin SM, Choi EJ, Moon SY (2016-06-29). "Prevalence of pathologies related to impacted mandibular third molars". SpringerPlus. 5 (1): 915. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2640-4. PMC 4927556. PMID 27386359.

- ^ a b Patil S, Halgatti V, Khandelwal S, Santosh BS, Maheshwari S (2014). "Prevalence of cysts and tumors around the retained and unerupted third molars in the Indian population". Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research. 4 (2): 82–87. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2014.07.003. PMC 4252379. PMID 25737923.

- ^ Borrás-Ferreres J, Sánchez-Torres A, Gay-Escoda C (December 2016). "Malignant changes developing from odontogenic cysts: A systematic review". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 8 (5): e622–e628. doi:10.4317/jced.53256. PMC 5149102. PMID 27957281.

- ^ Ghaeminia H, Nienhuijs ME, Toedtling V, Perry J, Tummers M, Hoppenreijs TJ, et al. (May 2020). "Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (5): CD003879. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003879.pub5. PMC 7199383. PMID 32368796.

- ^ Xiang X, Shi P, Zhang P, Shen J, Kang J (July 2019). "Impact of platelet-rich fibrin on mandibular third molar surgery recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Oral Health. 19 (1): 163. doi:10.1186/s12903-019-0824-3. PMC 6659259. PMID 31345203.

- ^ Dodson TB, Susarla SM (August 2014). "Impacted wisdom teeth". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014: 1302. PMC 4148832. PMID 25170946.

- ^ Kang F, Sah MK, Fei G (February 2020). "Determining the risk relationship associated with inferior alveolar nerve injury following removal of mandibular third molar teeth: A systematic review". Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 121 (1): 63–69. doi:10.1016/j.jormas.2019.06.010. PMID 31476533. S2CID 201805670.

- ^ Stanaitytė R, Trakinienė G, Gervickas A (2014). "Do wisdom teeth induce lower anterior teeth crowding? A systematic literature review". Stomatologija. 16 (1): 15–18. PMID 24824055.