Inertia

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

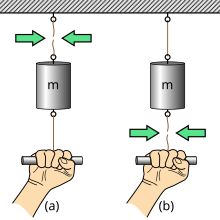

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes its velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newton in his first law of motion (also known as The Principle of Inertia).[1] It is one of the primary manifestations of mass, one of the core quantitative properties of physical systems.[2] Newton writes:[3][4][5][6]

LAW I. Every object perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, except insofar as it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon.

— Isaac Newton, Principia, The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, Translation by Cohen and Whitman, 1999[7]

In his 1687 work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Newton defined inertia as a property:

DEFINITION III. The vis insita, or innate force of matter, is a power of resisting by which every body, as much as in it lies, endeavours to persevere in its present state, whether it be of rest or of moving uniformly forward in a right line.[8]

History and development

[edit]Early understanding of inertial motion

[edit]Professor John H. Lienhard points out the Mozi – based on a Chinese text from the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) – as having given the first description of inertia.[9] Before the European Renaissance, the prevailing theory of motion in western philosophy was that of Aristotle (384–322 BCE). On the surface of the Earth, the inertia property of physical objects is often masked by gravity and the effects of friction and air resistance, both of which tend to decrease the speed of moving objects (commonly to the point of rest). This misled the philosopher Aristotle to believe that objects would move only as long as force was applied to them.[10][11] Aristotle said that all moving objects (on Earth) eventually come to rest unless an external power (force) continued to move them.[12] Aristotle explained the continued motion of projectiles, after being separated from their projector, as an (itself unexplained) action of the surrounding medium continuing to move the projectile.[13]

Despite its general acceptance, Aristotle's concept of motion[14] was disputed on several occasions by notable philosophers over nearly two millennia. For example, Lucretius (following, presumably, Epicurus) stated that the "default state" of the matter was motion, not stasis (stagnation).[15] In the 6th century, John Philoponus criticized the inconsistency between Aristotle's discussion of projectiles, where the medium keeps projectiles going, and his discussion of the void, where the medium would hinder a body's motion. Philoponus proposed that motion was not maintained by the action of a surrounding medium, but by some property imparted to the object when it was set in motion. Although this was not the modern concept of inertia, for there was still the need for a power to keep a body in motion, it proved a fundamental step in that direction.[16][17] This view was strongly opposed by Averroes and by many scholastic philosophers who supported Aristotle. However, this view did not go unchallenged in the Islamic world, where Philoponus had several supporters who further developed his ideas.

In the 11th century, Persian polymath Ibn Sina (Avicenna) claimed that a projectile in a vacuum would not stop unless acted upon.[18]

Theory of impetus

[edit]In the 14th century, Jean Buridan rejected the notion that a motion-generating property, which he named impetus, dissipated spontaneously. Buridan's position was that a moving object would be arrested by the resistance of the air and the weight of the body which would oppose its impetus.[19] Buridan also maintained that impetus increased with speed; thus, his initial idea of impetus was similar in many ways to the modern concept of momentum. Despite the obvious similarities to more modern ideas of inertia, Buridan saw his theory as only a modification to Aristotle's basic philosophy, maintaining many other peripatetic views, including the belief that there was still a fundamental difference between an object in motion and an object at rest. Buridan also believed that impetus could be not only linear but also circular in nature, causing objects (such as celestial bodies) to move in a circle. Buridan's theory was followed up by his pupil Albert of Saxony (1316–1390) and the Oxford Calculators, who performed various experiments which further undermined the Aristotelian model. Their work in turn was elaborated by Nicole Oresme who pioneered the practice of illustrating the laws of motion with graphs.

Shortly before Galileo's theory of inertia, Giambattista Benedetti modified the growing theory of impetus to involve linear motion alone:

[Any] portion of corporeal matter which moves by itself when an impetus has been impressed on it by any external motive force has a natural tendency to move on a rectilinear, not a curved, path.[20]

Benedetti cites the motion of a rock in a sling as an example of the inherent linear motion of objects, forced into circular motion.

Classical inertia

[edit]According to science historian Charles Coulston Gillispie, inertia "entered science as a physical consequence of Descartes' geometrization of space-matter, combined with the immutability of God."[21] The first physicist to completely break away from the Aristotelian model of motion was Isaac Beeckman in 1614.[22]

The term "inertia" was first introduced by Johannes Kepler in his Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae[23] (published in three parts from 1617 to 1621). However, the meaning of Kepler's term, which he derived from the Latin word for "idleness" or "laziness", was not quite the same as its modern interpretation. Kepler defined inertia only in terms of resistance to movement, once again based on the axiomatic assumption that rest was a natural state which did not need explanation. It was not until the later work of Galileo and Newton unified rest and motion in one principle that the term "inertia" could be applied to those concepts as it is today.[24]

The principle of inertia, as formulated by Aristotle for "motions in a void",[25] includes that a mundane object tends to resist a change in motion. The Aristotelian division of motion into mundane and celestial became increasingly problematic in the face of the conclusions of Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century, who argued that the Earth is never at rest, but is actually in constant motion around the Sun.[26]

Galileo, in his further development of the Copernican model, recognized these problems with the then-accepted nature of motion and, at least partially, as a result, included a restatement of Aristotle's description of motion in a void as a basic physical principle:

A body moving on a level surface will continue in the same direction at a constant speed unless disturbed.

Galileo writes that "all external impediments removed, a heavy body on a spherical surface concentric with the earth will maintain itself in that state in which it has been; if placed in a movement towards the west (for example), it will maintain itself in that movement."[27] This notion, which is termed "circular inertia" or "horizontal circular inertia" by historians of science, is a precursor to, but is distinct from, Newton's notion of rectilinear inertia.[28][29] For Galileo, a motion is "horizontal" if it does not carry the moving body towards or away from the center of the Earth, and for him, "a ship, for instance, having once received some impetus through the tranquil sea, would move continually around our globe without ever stopping."[30][31] It is also worth noting that Galileo later (in 1632) concluded that based on this initial premise of inertia, it is impossible to tell the difference between a moving object and a stationary one without some outside reference to compare it against.[32] This observation ultimately came to be the basis for Albert Einstein to develop the theory of special relativity.

Concepts of inertia in Galileo's writings would later come to be refined, modified, and codified by Isaac Newton as the first of his laws of motion (first published in Newton's work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, in 1687):

Every body perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon.[33]

Despite having defined the concept in his laws of motion, Newton did not actually use the term "inertia.” In fact, he originally viewed the respective phenomena as being caused by "innate forces" inherent in matter which resist any acceleration. Given this perspective, and borrowing from Kepler, Newton conceived of "inertia" as "the innate force possessed by an object which resists changes in motion", thus defining "inertia" to mean the cause of the phenomenon, rather than the phenomenon itself.

However, Newton's original ideas of "innate resistive force" were ultimately problematic for a variety of reasons, and thus most physicists no longer think in these terms. As no alternate mechanism has been readily accepted, and it is now generally accepted that there may not be one that we can know, the term "inertia" has come to mean simply the phenomenon itself, rather than any inherent mechanism. Thus, ultimately, "inertia" in modern classical physics has come to be a name for the same phenomenon as described by Newton's first law of motion, and the two concepts are now considered to be equivalent.

Relativity

[edit]Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity, as proposed in his 1905 paper entitled "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies", was built on the understanding of inertial reference frames developed by Galileo, Huygens and Newton. While this revolutionary theory did significantly change the meaning of many Newtonian concepts such as mass, energy, and distance, Einstein's concept of inertia remained at first unchanged from Newton's original meaning. However, this resulted in a limitation inherent in special relativity: the principle of relativity could only apply to inertial reference frames. To address this limitation, Einstein developed his general theory of relativity ("The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity", 1916), which provided a theory including noninertial (accelerated) reference frames.[34]

In general relativity, the concept of inertial motion got a broader meaning. Taking into account general relativity, inertial motion is any movement of a body that is not affected by forces of electrical, magnetic, or other origin, but that is only under the influence of gravitational masses.[35][36] Physically speaking, this happens to be exactly what a properly functioning three-axis accelerometer is indicating when it does not detect any proper acceleration.

Etymology

[edit]The term inertia comes from the Latin word iners, meaning idle or sluggish.[37]

Rotational inertia

[edit]A quantity related to inertia is rotational inertia (→ moment of inertia), the property that a rotating rigid body maintains its state of uniform rotational motion. Its angular momentum remains unchanged unless an external torque is applied; this is called conservation of angular momentum. Rotational inertia is often considered in relation to a rigid body. For example, a gyroscope uses the property that it resists any change in the axis of rotation.

See also

[edit]- Flywheel energy storage devices which may also be known as an Inertia battery

- General relativity

- Vertical and horizontal

- Inertial navigation system

- Inertial response of synchronous generators in an electrical grid

- Kinetic energy

- List of moments of inertia

- Mach's principle

- Newton's laws of motion

- Classical mechanics

- Special relativity

- Parallel axis theorem

References

[edit]- ^ Britannica, Dictionary. "definition of INERTIA". Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ Britannica, Science. "inertia physics". Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ Andrew Motte's English translation: Newton, Isaac (1846), Newton's Principia: the mathematical principles of natural philosophy (3rd edition), New York: Daniel Adee, p. 83

- ^ Andrew Motte's 1729 (1846) translation translated Newton's "nisi quatenus" erroneously as unless instead of except insofar. Hoek, D. (2023). "Forced Changes Only: A New Take on Inertia". Philosophy of Science. 90 (1): 60–73. arXiv:2112.02339. doi:10.1017/psa.2021.38. hdl:10919/113143.

- ^ "What Newton really meant | Daniel Hoek". IAI TV - Changing how the world thinks. 2023-08-17. Retrieved 2023-09-29.

- ^ Pappas, Stephanie (5 September 2023). "Mistranslation of Newton's First Law Discovered after Nearly Nearly 300 Years". Scientific American.

- ^ Newton, I. (1999). The Principia, The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Translated by Cohen, I.B.; Whitman, A. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29087-7.

- ^ Andrew Motte's English translation: Newton, Isaac (1846), Newton's Principia: the mathematical principles of natural philosophy (3rd edition), New York: Daniel Adee, p. 73

- ^ "No. 2080 The Survival of Invention". www.uh.edu.

- ^ Aristotle: Minor works (1936), Mechanical Problems (Mechanica), University of Chicago Library: Loeb Classical Library Cambridge (Mass.) and London, p. 407,

...it [a body] stops when the force which is pushing the travelling object has no longer power to push it along...

- ^ Pages 2 to 4, Section 1.1, "Skating", Chapter 1, "Things that Move", Louis Bloomfield, Professor of Physics at the University of Virginia, How Everything Works: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary, John Wiley & Sons (2007), hardcover, ISBN 978-0-471-74817-5

- ^ Byrne, Christopher (2018). Aristotle's Science of Matter and Motion. University of Toronto Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4875-0396-3. Extract of page 21

- ^ Aristotle, Physics, 8.10, 267a1–21; Aristotle, Physics, trans. by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye, 'projectile' Archived 2007-01-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Darling, David (2006). Gravity's arc: the story of gravity, from Aristotle to Einstein and beyond. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 17, 50. ISBN 978-0-471-71989-2.

- ^ Lucretius, On the Nature of Things (London: Penguin, 1988), pp. 80–85, 'all must move'

- ^ Sorabji, Richard (1988). Matter, space and motion : theories in antiquity and their sequel (1st ed.). Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0801421945.

- ^ "John Philoponus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 8 June 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Espinoza, Fernando. "An Analysis of the Historical Development of Ideas About Motion and its Implications for Teaching". Physics Education. Vol. 40(2). Medieval thought.

- ^ Jean Buridan: Quaestiones on Aristotle's Physics (quoted at Impetus Theory)

- ^ Stillman Drake. Essays on Galileo etc. Vol 3. p. 285.

- ^ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. pp. 367–68. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- ^ van Berkel, Klaas (2013), Isaac Beeckman on Matter and Motion: Mechanical Philosophy in the Making, Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 105–110, ISBN 9781421409368

- ^ Lawrence Nolan (ed.), The Cambridge Descartes Lexicon, Cambridge University Press, 2016, "Inertia.", p. 405

- ^ Biad, Abder-Rahim (2018-01-26). Restoring the Bioelectrical Machine. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 9781365447709.[permanent dead link]

- ^ 7th paragraph of section 8, book 4 of Physica

- ^ Nicholas Copernicus, The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, 1543

- ^ Drake, Stillman. "Galilei's presentation of his principle of inertia, p. 113". Retrieved 2022-07-31.

- ^ See Alan Chalmers article "Galilean Relativity and Galileo's Relativity", in Correspondence, Invariance and Heuristics: Essays in Honour of Heinz Post, eds. Steven French and Harmke Kamminga, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1991, pp. 199–200, ISBN 0792320859. Chalmers does not, however, believe that Galileo's physics had a general principle of inertia, circular or otherwise. page 199

- ^ Dijksterhuis E.J. The Mechanisation of the World Picture, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1961, p. 352

- ^ Drake, Stillman. "Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo, p. 113-114". Retrieved 2022-07-31.

- ^ According to Newtonian mechanics, if a projectile on a smooth spherical planet is given an initial horizontal velocity, it will not remain on the surface of the planet. Various curves are possible depending on the initial speed and the height of the launch. See Harris Benson University Physics, New York 1991, page 268. If constrained to remain on the surface, by being sandwiched, say, in between two concentric spheres, it will follow a great circle on the surface of the earth, i.e. will only maintain a westerly direction if fired along the equator. See "Using great circles" Using great circles

- ^ Galileo, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, 1632 (full text).

- ^ Andrew Motte's English translation:Newton, Isaac (1846), Newton's Principia : the mathematical principles of natural philosophy, New York: Daniel Adee, p. 83 This usual statement of Newton's law from the Motte-Cajori translation, is however misleading giving the impression that 'state' refers only to rest and not motion whereas it refers to both. So the comma should come after 'state' not 'rest' (Koyre: Newtonian Studies London 1965 Chap III, App A)

- ^ Alfred Engel English Translation:Einstein, Albert (1997), The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity (PDF), New Jersey: Princeton University Press, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2015, retrieved 30 May 2014

- ^ Max Born; Günther Leibfried (1962). Einstein's Theory of Relativity. New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 315. ISBN 0-486-60769-0.

inertial motion.

- ^ Max Born (1922). "Einstein's Theory of Relativity - inertial motion, p. 252". New York, E. P. Dutton and company, publishers.

- ^ "inertia | Etymology, origin and meaning of inertia by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

Further reading

[edit]- Butterfield, H (1957), The Origins of Modern Science, ISBN 0-7135-0160-X.

- Clement, J (1982), "Students' preconceptions in introductory mechanics", American Journal of Physics vol 50, pp 66–71

- Crombie, A C (1959), Medieval and Early Modern Science, vol. 2.

- McCloskey, M (1983), "Intuitive physics", Scientific American, April, pp. 114–123.

- McCloskey, M & Carmazza, A (1980), "Curvilinear motion in the absence of external forces: naïve beliefs about the motion of objects", Science vol. 210, pp. 1139–1141.

- Pfister, Herbert; King, Markus (2015). Inertia and Gravitation. The Fundamental Nature and Structure of Space-Time. Vol. The Lecture Notes in Physics. Volume 897. Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-15036-9. ISBN 978-3-319-15035-2.

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2001a). "Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's Motion in Context". Science in Context. 14 (1–2). Cambridge University Press: 145–163. doi:10.1017/S0269889701000060. S2CID 145372613.

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2001b). "Freeing Astronomy from Philosophy: An Aspect of Islamic Influence on Science". Osiris. 2nd Series. 16 (Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions): 49–64 & 66–71. Bibcode:2001Osir...16...49R. doi:10.1086/649338. S2CID 142586786.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Inertia at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Inertia at Wikiquote- Why Does the Earth Spin? (YouTube)