Fitzcarraldo

| Fitzcarraldo | |

|---|---|

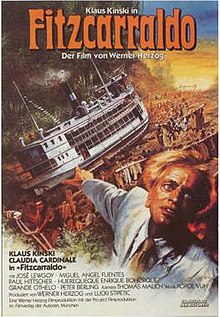

German release poster | |

| Directed by | Werner Herzog |

| Written by | Werner Herzog |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Thomas Mauch |

| Edited by | Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus |

| Music by | Popol Vuh |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Filmverlag der Autoren (West Germany) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 157 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | DM 14 million[1] |

Fitzcarraldo (/fɪtskə'raldo/) is a 1982 West German epic adventure-drama film written, produced, and directed by Werner Herzog, and starring Klaus Kinski as would-be rubber baron Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, an Irishman known in Peru as Fitzcarraldo, who is determined to transport a steamship over the Andes mountains to access a rich rubber territory in the Amazon basin. The character was inspired by Peruvian rubber baron Carlos Fitzcarrald, who once transported a disassembled steamboat over the Isthmus of Fitzcarrald.

The film had a troubled production, chronicled in the documentary Burden of Dreams (1982). Herzog had his crew attempt to manually haul the 320-ton steamship up a steep hill, leading to three injuries. The film's original star Jason Robards became sick halfway through filming, so Herzog hired Kinski, with whom he had previously clashed violently during production of Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), and Woyzeck (1979). Their fourth collaboration fared no better. When shooting was nearly complete, the chief of the Machiguenga tribe, whose members were used extensively as extras, asked Herzog if they should kill Kinski for him. Herzog declined.[2]

Plot

[edit]In the early part of the 20th century, Iquitos, Peru, a small city east of the Andes in the Amazon basin, is experiencing rapid growth due to a rubber boom, and many Europeans and North African Sephardic Jewish immigrants are settling in the city, bringing their cultures with them. One immigrant, an Irishman named Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (known by the locals as "Fitzcarraldo"), is a lover of opera and a great fan of the internationally-renowned Italian tenor Enrico Caruso. He dreams of building an opera house in Iquitos, but, although he has an indomitable spirit, he has little capital. The Peruvian government has parceled up the areas in the Amazon basin known to contain rubber trees. However, the best parcels having already been leased to private companies for exploitation, Fitzcarraldo has been trying and failing to make the money to bring opera to Iquitos by various other means, including an ambitious attempt to construct a Trans-Andean Railway.

A rubber baron shows Fitzcarraldo a map and explains that, while the only remaining unclaimed parcel in the area is on the Ucayali River, a major tributary of the Amazon, it is cut off from the Amazon (and access to Atlantic ports) by a lengthy section of rapids. Fitzcarraldo notices that the Pachitea River, another Amazon tributary, comes within several hundred meters of the Ucayali upstream of the parcel.[a] He leases the inaccessible parcel from the government, and his paramour, Molly, a successful brothel owner, funds his purchase of an old steamship, which he christens the SS Molly Aida, from the rubber baron. After fixing up the boat, Fitzcarraldo recruits a crew and takes off up the Pachitea, which is largely unexplored because of the hostile indigenous people who live on its banks.

Fitzcarraldo intends to go to the closest point between the Ucayali and the Pachitea, pull his three-deck, 320-ton steamship up the muddy 40° hillside, and portage it from one river to the next.[3] He plans to use the ship to collect rubber harvested along the upper Ucayali and then transport the rubber over to the Pachitea and, on different ships, down to market at Atlantic ports.

Soon after they enter indigenous territory, the majority of Fitzcarraldo's crew, who are unaware of his full plan, abandon the expedition, leaving only the captain, engineer, and cook. The natives are impressed by the steamship and, once they make contact, agree to help Fitzcarraldo without asking many questions. After months of work and great struggles, they successfully pull the ship over the mountain using a complex system of pulleys and aided by the ship's anchor windlass. The crew falls asleep after a drunken celebration, and the chief of the natives severs the rope securing the ship to the shore. Fitzcarraldo awakens as the boat is going through the Ucayali rapids, and is unable to stop it. The ship does not sustain any major damage, but Fitzcarraldo is forced to abandon his quest. Before returning to Iquitos, he learns that the natives helped him move the ship so they could attempt to appease the river gods by shooting the rapids in the enormous ship.

Despondent, Fitzcarraldo sells the steamship back to the rubber baron, but there is time before the title changes hands for him to send for a European opera company that he hears is in Manaus. Lacking an opera house, they construct their sets on the deck of the ship, and the entire city of Iquitos comes down to the riverbank to watch as Fitzcarraldo floats it by, managing to bring opera to the city after all.

Cast

[edit]- Klaus Kinski as Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (aka Fitzcarraldo)

- Claudia Cardinale as Molly

- José Lewgoy as Don Aquilino

- Miguel Ángel Fuentes as Cholo

- Paul Hittscher as Captain Paul Resenbrink (aka Orinoco Paul)

- Huerequeque Enrique Bohórquez as Huerequeque

- Grande Otelo (credited as Grande Othelo) as the station master

- Peter Berling as the opera manager in Manaus

- David Pérez Espinosa as the chief of the Campa Indians

- Milton Nascimento as the doorman at the opera house in Manaus

- Ruy Polanah as a rubber baron

- Salvador Godínez as the old missionary

- Dieter Milz as the young missionary

- William Rose (credited as Bill Rose) as the notary

- Leôncio Bueno as the jailer

- Costante Moret as Enrico Caruso

- Jean-Claude Dreyfus as Sarah Bernhardt

Production

[edit]

Fitzcarraldo is considered one of the most difficult productions in the history of cinema.[4]

The story was inspired by the historical figure of Peruvian rubber baron Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald. In the 1890s, Fitzcarrald arranged for the transport of a steamship across an isthmus from one river into another, but it weighed only 30 tons (rather than over 300), and was carried over in pieces to be reassembled at its destination.[3][5]

In his autobiographical film Portrait Werner Herzog (1986), Herzog said that he concentrated in Fitzcarraldo on the physical effort of transporting the ship, partly inspired by the engineering feats of ancient standing stones. The film production was an incredible ordeal, and famously involved moving a 320-ton steamship over a hill. This was filmed without the use of special effects. Herzog believed that no one had ever performed a similar feat in history, and likely never will again, calling himself "Conquistador of the Useless".[6] Three similar-looking ships were bought for the production and used in different scenes and locations, including scenes that were shot aboard the ship while it crashed through rapids. The most violent scenes in the rapids were shot with a model of the ship.[7] Three of the six people involved in the filming of this sequence were injured.[citation needed]

Jason Robards was originally cast in the title role, but he became ill with dysentery after completing forty percent of the film and was subsequently forbidden by his doctors to return to Peru to finish. Herzog considered replacing Robards with Jack Nicholson, or playing Fitzcarraldo himself, before Klaus Kinski, with whom Herzog had worked on three previous films, accepted the role. Due to the delay in production, Mario Adorf was no longer available to play the role of the ship's captain, which was recast, and Mick Jagger had to leave to tour with the Rolling Stones, so Herzog wrote the character of Fitzcarraldo's assistant Wilbur out of the script.

Kinski displayed erratic behavior throughout the production and fought virulently with Herzog and other members of the crew. A scene from Herzog's documentary about the actor, My Best Fiend (1999), shows Kinski raging at production manager Walter Saxer over such matters as the quality of the food. Herzog has noted that the native extras were greatly upset by the actor's behavior, while Kinski claimed to feel close to them. In My Best Fiend, Herzog says that one of the native chiefs offered, in all seriousness, to kill Kinski for him, but that he declined because he needed the actor to complete filming. According to Herzog, he exploited these tensions. For example, in a scene in which the ship's crew is eating dinner while surrounded by the natives, the clamor the chief incites over Fitzcarraldo was inspired by actual hatred of Kinski.[8]

Locations used in the film include: Manaus, Brazil; Iquitos, Peru; Pongo de Mainique, Peru; and an isthmus between the Urubamba and the Camisea rivers in Peru (at -11.737294,-72.934542, 36 miles west of the actual Isthmus of Fitzcarrald).

Herzog's first version of the story was published as Fitzcarraldo: The Original Story (1982) by Fjord Press (ISBN 0-940242-04-4). He made alterations while writing the screenplay.[citation needed]

Deaths, injuries and accusations of exploitation

[edit]The production was affected by numerous injuries and the deaths of several indigenous extras who were hired to work on the film as laborers. Two small plane crashes occurred during the film's production, which resulted in a number of injuries, including one case of paralysis.[9] Another incident involved a local Peruvian logger who, after being bitten by a venomous snake, amputated his own foot with a chainsaw so as to prevent the spread of the venom, thus saving his life.[9][10]

Herzog has been accused of exploiting indigenous people during the making of the film, and comparisons have been made between Herzog and Fitzcarraldo himself. In 1982, Michael F. Brown, now a professor of anthropology at Williams College, claimed in the magazine The Progressive that, while Herzog originally got along with the Aguaruna people, some of whom were hired as extras and laborers, relations deteriorated when Herzog began the construction of a village on Aguaruna land. He allegedly failed to consult the tribal council and attempted to obtain protection from the local militia when the tribe turned violent. Aguaruna men burned down the film set in December 1979, reportedly careful to avoid casualties,[11] and it took Herzog many months to find another suitable location.

Music

[edit]The soundtrack album (released in 1982) contains music by Popol Vuh, taken from the albums Die Nacht der Seele (1979) and Sei still, wisse ich bin (1981),[12][13] as well as performances by Enrico Caruso and others. The film uses excerpts from Verdi's Ernani, Leoncavallo's Pagliacci ("Ridi, Pagliaccio"), Puccini's La bohème, Bellini's I puritani, and Strauss' Death and Transfiguration.

Reception

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film four (out of four) stars in his original 1982 review, and he added it to his "Great Movie" collection in 2005.[14][15] Ebert compared Fitzcarraldo to films like Apocalypse Now (1979) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), noting that "we are always aware both of the film, and of the making of the film", and concluding that "[t]he movie is imperfect, but transcendent".[16]

Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited Fitzcarraldo as one of his favorite films.[17][18]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 75% "Fresh" rating based on 32 reviews, with an average score of 7.5 out of 10.[19]

Awards

[edit]Fitzcarraldo won the German Film Prize in Silver for Best Feature Film. It was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Film, the Palme d'Or award of the Cannes Film Festival, and the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Herzog won the award for Best Director at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival.[20] The film was selected as the West German entry for Best Foreign Language Film at the 55th Academy Awards, but did not make the final shortlist of five nominees.[21]

Related works

[edit]Les Blank's documentary Burden of Dreams (1982), filmed during the production of Fitzcarraldo, documents its many hardships. Blank's work contains some of the only surviving footage of Robards' and Jagger's performances in the early filming of Fitzcarraldo. Herzog later used portions of this work in his documentaries: Portrait Werner Herzog (1986) and My Best Fiend (1999). Burden of Dreams has many scenes documenting the arduous transport of the ship over the mountain.

Herzog's personal diaries from the production were published in 2004 as the book Conquest of the Useless. The book includes an epilogue with Herzog's views on the Peruvian jungle 20 years later.[22]

References

[edit]In her 1983 parody "From the Diary of Werner Herzog" in The Boston Phoenix, Cathleen Schine describes the history of a fictitious film, Fritz: Commuter, as "a nightmarish tale of a German businessman obsessed with bringing professional hockey to Westport, Connecticut".[23]

Glen Hansard wrote a song entitled "Fitzcarraldo", which appears on The Frames' 1995 album of the same name. On their live album Set List, Hansard says that Herzog's film inspired this song.

The film is referred to in the Simpsons episode "On a Clear Day I Can't See My Sister" (2005), in which the students are forced to pull their bus up a mountain. Üter complains, "I feel like I'm Fitzcarraldo!", and Nelson replies, "That movie was flawed!", punching Üter in the stomach.[24] The title of a later episode of the series, "Fatzcarraldo" (2017), references the title of the film and also parodies aspects of its plot.

See also

[edit]- List of submissions to the 55th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of German submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- Carlos Fitzcarrald

- Isthmus of Fitzcarrald

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is fictional. The Pachitea is a tributary of the Ucayali, not a third river, and their confluence is nearly 500 kilometers south of Iquitos. The true map looks nothing like the one Fitzcarraldo draws.

References

[edit]- ^ Rumler, Fritz (24 August 1981). ""Eine Welt, in der Schiffe über Berge fliegen"". Der Spiegel. No. 35/1981. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Klaus Kinski Wutausbruch am Filmset von 'Fitzcarraldo' - Section from the Movie "Mein liebster Feind" (in German), retrieved 6 December 2022

- ^ a b Blank, Les (1982). "English captions of documentary Burden of Dreams from 1:11:25 to 1:12:40". Burden of Dreams. Archived from the original on 1 November 2006.

[Werner Herzog:] Well, the boat that [Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald] actually pulled across was only 30 tons. ... Besides, they, uh, disassembled it in about 14 or 15 parts ... The central metaphor of my film is that they haul a ship over what's essentially an impossibly steep hill. ... [Les Blank:] a complicated system to pull Herzog's ship over the hill ... But the system is designed for a 20-degree slope. Herzog insists on 40 degrees.

- ^ "Two cinematographic gems hidden for almost four decades will see the light of day in Play-Doc 2021". Play-Doc. 5 August 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Blank, Les (1982). "English captions of documentary Burden of Dreams from 0:02:09 to 0:02:36". Burden of Dreams. Archived from the original on 31 October 2006.

[Werner Herzog:] There was a historical figure whose name was Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald, a 'caucho' baron. I must say the story of this caucho baron did not interest me so much. What interested me more was one single detail. That was, uh, that he crossed an isthmus, from one river system into another, uh, with a boat. They disassembled the boat and – and put it together again on the other river.

- ^ Herzog, Werner (2001). Herzog on Herzog. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-20708-1.

- ^ "Fitzcarraldo 1982 | modelshipsinthecinema.com". Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Herzog, Werner (1999). My Best Fiend, 59:20-59:50

- ^ a b "It's past time we condemned Fitzcarraldo". Films Ranked. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Jaremko-Greenwold, Anya; Jaremko-Greenwold, Anya (4 September 2015). "11 Craziest Things That Have Happened During the Making of Werner Herzog's Films". Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Brown, Michael F. (August 1982). "Art of Darkness" (PDF). The Progressive: 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ enricobassi.it Archived 2011-04-04 at the Wayback Machine Fitzcarraldo soundtrack album

- ^ Fitzcarraldo soundtrack album at Discogs (list of releases)

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Fitzcarraldo". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Fitzcarraldo (1982)". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Fitzcarraldo (1982)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ Lee Thomas-Mason (12 January 2021). "From Stanley Kubrick to Martin Scorsese: Akira Kurosawa once named his top 100 favourite films of all time". Far Out. Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Akira Kurosawa's Top 100 Movies!". Archived from the original on 27 March 2010.

- ^ "Fitzcarraldo | Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Fitzcarraldo". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- ^ Addiego, Walter (3 August 2009). "'Conquest of the Useless,' by Werner Herzog". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Schine, Cathleen (18 January 1983). "From the diary of Werner Herzog". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "On a Clear Day I Can't See My Sister". IMDb.com. 6 March 2005.

External links

[edit]- 1982 films

- 1980s adventure drama films

- German adventure drama films

- German epic films

- Seafaring films

- Films shot in Manaus

- Films shot in Peru

- Films set in Brazil

- Films set in Peru

- Films set in the 1890s

- 1980s German-language films

- West German films

- Films directed by Werner Herzog

- Films scored by Popol Vuh (band)

- Films set in jungles

- 1982 drama films

- 1980s German films

- 1982 independent films

- German independent films

- Cultural depictions of Sarah Bernhardt