Spirit house

A spirit house is a shrine to the protective spirit of a place that is found in the Southeast Asian countries of Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. They are normally in the form of small roofed structure mounted on a pillar or a dais, and can range in size from small platforms to houses large enough for people to enter. Spirit houses are intended to provide a shelter for spirits that could cause problems for the people if not appeased. They often include images or carved statues of people and animals. Votive offerings are left at them to propitiate the spirits; more elaborate installations include an altar for this purpose.

In mainland Southeast Asia, most houses and businesses have a spirit house placed in an auspicious spot, most often in a corner of the property. The location may be chosen after consultation with a Brahmin priest. Spirit houses are known as နတ်စင် (nat sin) or နတ်ကွန်း (nat kun) in Burmese; ศาลพระภูมิ (san phra phum, 'house of the guardian spirit') in Thai; and រានព្រះភូមិ (rean preah phum, 'shrine for the guardian-spirit') or រានទេវតា (rean taveda) in Khmer.

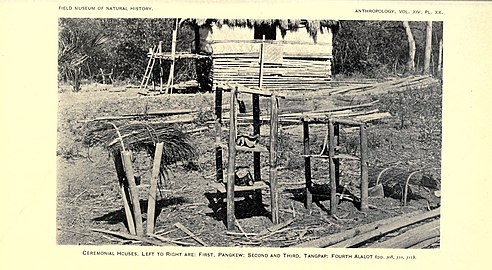

In maritime Southeast Asia, spirit houses are connected to the various traditional animistic rituals involving spirits. In the Philippines, spirit houses are dedicated to ceremonies or offerings involving the anito spirits. They are also referred to as shrines. They are known magdantang in Visayan; ulango or simbahan in Tagalog; tangpap, pangkew, or alalot (for various small roofed altars), and balaua or kalangan (for larger structures) in Itneg; maligai in Subanen; tenin in Tiruray; and buis (for those built near roads and villages) and parabunnian (for those built near rice fields) in Bagobo.[1][2][3]

In Chinese Spirit houses are called 土地神屋 or Tudigong House, representing a link between the concept and the concept of an Earth Temple dedicated to a landlord deity or a Tudigong

In Tamil Nadu, spirit houses and shrines house local tutelary spirits, guardian deities, and deified ancestors who derive from ancient Dravidian animistic beliefs.[4][5] They tend to be located on the periphery of villages, known as the "katu," due to the belief that these spirits are "too dangerous and unpredictable to [have] reside in the village... and seem to be disturbed by the sounds of village life."[6] Many of these spirit houses are dedicated to the spirit of a deified hero, especially— Madurai Veeran, Karuppuswami, or Aiyanar.[7] Offerings of bananas, coconuts, oil lamps, meat, and alcohol are routinely left at these shrines to ensure the health and safety of the village. This starkly contrasts the Vedic Hindu practice of only offering vegetarian foods to deities.[8] As a result of countless Tamils falling into the British Raj's indenture system, these shrines have spread throughout the Indian diaspora.[9]

In Kerala, each family home complex (for Nairs and Ezhavas), known as a tharavadu, has a spirit house located towards the northeast corner. Known as "kavu" or "sarpa kavukal," these shrines consist of a small grove with symbolic houses and carved stone effigies of guardian nagas, and other "gods, spirits, yakshi, [or] ancestors."[10] The Malayali people traditionally believe that the construction and maintenance of these sacred shrines keeps tutelary spirits docile and can even serve as atonement for "angry serpent gods [who were]... left unattended."[11] Spirits of the kavu are most commonly offered "raw rice, unbroken coconut fruits, betel leaves, and areca nut," as well as an "oil lamp in front of the deity at dusk."[12][13] Occasionally, these kavu serve as locations for shamanistic rituals known as "pampin kalam" where mediums channel the deities and perform sacred rites around hand-drawn mandalas made from coloured powder.[14]

Spirit house offerings

[edit]In Cambodia, the most common offering are fruits (e.g. banana, orange, grape; some people even offer different fruits at the same time.) In neighbouring Thailand however, it is a long-standing tradition to leave offerings of food and drink at the spirit house. Rice, bananas, coconuts, and desserts are common offerings. Most ubiquitous is red, strawberry-flavoured Fanta.[15] The idea seems to be that friendly spirits will congregate to enjoy free food and drink and their presence will serve to keep more malign spirits at bay. The popularity of red Fanta offerings has existed for decades. Opinions as to "why Fanta?" vary. Most point to the significance of the colour red, reminiscent of animal sacrifice, or perhaps related to the practice of anchoring red incense sticks in a glass of water which promptly tints the water red. Sweetness is explained by the observation that sweet spirits naturally have sweet tooths.[16]

Parts

[edit]Parts of spirit houses include

- A raised pedestal base

- A roof

- An altar

- Sacred objects inside such as buddha statues

Gallery

[edit]-

A nat sin in downtown Yangon, Burma

-

Spirit house, Bangkok

-

Spirit houses at a private house, Phetchaburi, Thailand

-

Spirit houses protect a business, Thailand

-

Spirit house, Hua Hin

-

Cambodian-style spirit houses.

-

Ceremonial spirit houses among the Itneg (left to right) the pangkew, two tangpap, and an alalot (1922, Philippines)

-

Kalangan spirit house, Itneg people (1922, Philippines)

-

A spirit house in Livingstonia, Malawi (c. 1910)

-

A Shrine of Peter and Paul, Ayutthaya, Thailand

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ William Henry Scott (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 9715501354.

- ^ A. L. Kroeber (1918). "The History of Philippine Civilization as Reflected in Religious Nomenclature". Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. XXI (Part II): 35–37.

- ^ Fay-Cooper Cole & Albert Gale (1922). "The Tinguian; Social, Religious, and Economic life of a Philippine tribe". Field Museum of Natural History: Anthropological Series. 14 (2): 235–493.

- ^ Slaczka, Anna (2016). ""Temple Guardians and 'Folk Hinduism' in Tamil South India: A Bronze Image of the 'Black God' Karuppannasamy in the Rijksmuseum"". The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 64 (1): 67–68. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Elmore, Wilder Theodore (1915). Dravidian Gods in Modern Hinduism: A Study of the Local and Village Deities of southern India (PDF) (15 ed.). Hamilton, New York: Published by the author. pp. 16–19. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Slaczka, Anna (2016). ""Temple Guardians and 'Folk Hinduism' in Tamil South India: A Bronze Image of the 'Black God' Karuppannasamy in the Rijksmuseum"". The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 64 (1): 68. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Slaczka, Anna (2016). ""Temple Guardians and 'Folk Hinduism' in Tamil South India: A Bronze Image of the 'Black God' Karuppannasamy in the Rijksmuseum"". The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 64 (1): 67. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Arumugam, Indira (2021). Laying Out Feast-Offerings: Offering Meat, Feasting Together and Sharing with the Gods (PDF). Singapore: National University of Singapore. p. 282. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Bose, Mansi (2022). "Religious Divergence and Ethnic Syncretism: Transitions in Kali Mai Worship in Postcolonial Trinidad". The Achievers Journal- University of Lucknow. 8 (2454–2296): 24. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ K, Murugan; VS, Ramachandran; K, Swarupanandan; M, Remesh (2008). "Socio-cultural perspectives to the sacred groves and serpentine worship in Palakkad district, Kerala". CSIR. 1: 455–462. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ K, Murugan; VS, Ramachandran; K, Swarupanandan; M, Remesh (2008). "Socio-cultural perspectives to the sacred groves and serpentine worship in Palakkad district, Kerala". CSIR. 1: 457. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ K, Murugan; VS, Ramachandran; K, Swarupanandan; M, Remesh (2008). "Socio-cultural perspectives to the sacred groves and serpentine worship in Palakkad district, Kerala". CSIR. 1: 457. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Rajagopalan, L. S. (1981). The Pulluvans and their Music (PDF) (L1 ed.). The Music Academy Madras- 14: T.S. Parthasarathy. p. 73. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Rajagopalan, L. S. (1981). The Pulluvans and their Music (PDF) (L1 ed.). The Music Academy Madras- 14: T.S. Parthasarathy. p. 72. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Bengali, Shashank (2019-04-18). "The spirit houses of Bangkok keep watch over a frenetic modern Thai city". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ^ Winn, Patrick (2017-04-06). "In Thailand, blood sacrifice is out. Strawberry Fanta is in". Public Radio International (PRI). Retrieved 18 August 2018.