Candido Portinari

Candido Portinari | |

|---|---|

Portinari in 1962 | |

| Born | Candido Portinari December 29, 1903 Brodowski, São Paulo, Brazil |

| Died | February 6, 1962 (aged 58) Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Known for | painter |

| Notable work | O Mulato, Café, Meninos de Brodowski, Guerra e Paz |

| Movement | Modern Art |

Candido Portinari (December 29, 1903 – February 6, 1962) was a Brazilian painter. He is considered one of the most important Brazilian painters as well as a prominent and influential practitioner of the neo-realism style in painting.

Portinari painted more than five thousand canvases, from small sketches to monumental works such as the Guerra e Paz panels, which were donated to the United Nations Headquarters in 1956. Portinari developed a social preoccupation throughout his oeuvre and maintained an active life in the Brazilian cultural and political worlds.

Life and career

[edit]Born to Giovan Battista Portinari and Domenica Torquato, Italian immigrants from Chiampo Vicenza, Veneto, in a coffee plantation near Brodowski, in São Paulo.[1] Growing up on a coffee plantation of dark soil and blue sky, Portinari gained his inspiration from the homeland he loved. In the majority of his later paintings, murals and frescoes, he used the colour blue and many browns and reds because this was the color of his home.

One of Portinari's beginner jobs was drawing photographs where he closely captured the exact image using paints and then enlarging the photos. These sold successfully because the resemblance was astounding. Portinari then studied at the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes (National School of Fine Arts) in Rio de Janeiro. In 1923, 1925 and 1927 Portinari won prizes at the Salon, and in 1928 he got a scholarship offered by the Brazilian government to study in Europe for three years.[1] During his time in Europe Portinari did little painting, but studied the works of various European artists, visited museums, and met his future wife, Maria Martinelli. He came back to Brazil fully set on conveying the true Brazilian lifestyle and capturing the pain and struggles of his people through his art.[2]

After his return, Portinari began portraying the reality of Brazil, from its natural beauties to the harsh lives of the country's most impoverished populations, pursuing an amalgamation of his academic formation with the modernist avant-gardes. Portinari remained himself and didn't allow his new experiences and new outlooks changed him. His roots remained important to him and he strove to portray this in his paintings; the true Brazilian spirit. He wanted the world to see the harsh reality of living conditions in Brazil and the struggle for survival. Strength, hard work, independence and authenticity shows through in almost every one of his works.[3]

In 1939, Portinari exhibited at the New York World's Fair. In the following year, Portinari had for the first time a canvas displayed at the Museum of Modern Art. The rise of fascism in Europe, the wars and the close contact with Brazilian problematic society, reaffirmed the social character of his work, as well as conducting him to political engagement.

He joined the Brazilian Communist Party and stood for deputy in 1945[4] and for senator in 1947,[5] but had to flee to Uruguay to escape the persecution of communists during the government of Eurico Gaspar Dutra. In 1951, the first São Paulo Art Biennial dedicated a special room for his works. He returned to Brazil in the following year, after a declaration of general amnesty from the government. In 1956, after the United Nations had appealed to its affiliated countries for the donation of a work of art to the organization's new headquarters. Brazil designated Portinari for the task, who took four years and around 180 studies to complete the painting. Dag Hammarskjöld, UN Secretary-General, named the work "the most important monumental work of art donated to the UN".[2]

Even after being warned by the doctor of the risks of the toxins and poisoning, he didn't give up and continued to paint. Portinari suffered from ill health during the last decade of his life. He died in Rio de Janeiro in 1962 as a result of lead poisoning from his paints.[2][failed verification][6]

On December 20, 2007, his painting O Lavrador de Café[7] was stolen from the São Paulo Museum of Art along with Pablo Picasso's Portrait of Suzanne Bloch.[8] The paintings remained missing until January 8, 2008, when they were recovered in Ferraz de Vasconcelos by the Police of São Paulo. The paintings were returned, undamaged, to the São Paulo Museum of Art.[9]

There were a number of commemorative events in the centenary of his birth in 2003, including an exhibition of his work in London.

Style

[edit]

Portinari's works comprehend a strong will to represent Brazilian people and their traits. Portinari himself said he would "paint that people with that clothing and that color". According to Antonio Callado, Portinari's oeuvre demonstrate a "monumental book of art which teaches Brazilians to love more their land".[2]

Portinari was capable of transcending his original academic formation by experiencing with and absorbing modernist techniques and styles, which fundamentally created his painting personality. The range and sweep of his output includes paintings depicting rural and urban labour, refugees fleeing the hardships of Brazil's rural north-east; and, despite these major and better known aspects of his work, treatments of the key events in the history of Brazil since the arrival of the Portuguese in 1500, images of childhood, portraits of members of his family and leading Brazilian intellectuals, illustrations for books and tiles decorating the Church of São Francisco at Pampulha, Belo Horizonte.

His career coincided with and included collaboration with Oscar Niemeyer amongst others. Portinari's works can be found in galleries and settings in Brazil and abroad, ranging from the family chapel in his childhood home in Brodowski to his panels Guerra e Paz (War and Peace) in the United Nations building in New York and four murals in the Hispanic Reading Room of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.[10]

Contribution to Brazilian modernism

[edit]As previously mentioned, Candido Portinari came from a poor immigrant family.[11] This allowed him to have a unique perspective on Brazilian culture and what it meant to truly be Brazilian. This is important because he was a prominent artist during the Brazilian Modernism era.[12] As such, his perspective gave a more proud and dignified view of the workers at that time. While other artists like Lasar Segall with Bananal and Tarsila do Amaral with Workers provided a picture of the workers that removed personality and made each individual anonymous, Portinari did the opposite. For example, in his painting, The Mestizo, he paints a character that looks strong, competent, and noble. In this, he is demonstrating that the workers were not broken. Instead, they were proud and independent. Portinari used his culture and life experience to add to the explanation of what Brazil is in a distinctive style.

Murals

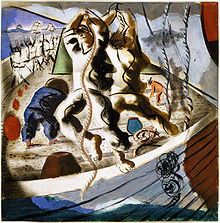

[edit]In Cocoa (1938) Portinari depicts workers on the coffee plantations. A woman is seen in the back balancing a crate on her head and there is a child in the painting. This was meant to signify that children were present during this hard work as well, and were encouraged to help the parents. Land was given to families in return for their labor on the plantations where they took care of their share. Here too is included the use of blues and oranges to truly capture the significance of Brazil, which was Portinari's desire. This artwork was described by saying “Brazil is being rescued from obscurity by ‘Portinari’s Coffee’.”[13]

Coffee (National Museum of Fine Arts, 1935) represents strong and resourceful workers. Their big hands and feet show they were strong and did not fear hard work.[13] The people worked together to preserve their lands and survive. This painting is also a great depiction of “realism” because of how he captures his people with the short bodies, rounder heads and the brown and red hues of the land.

In The Mestizo (1934) he tries to present not just a portrait but an individual type of person.[14] Portinari shows that Brazilian workers were tough and proud of their work because in the background of the Mestizo are seen the fields and all their hard work; his proud stance portrays confidence and strength.

War and Peace (Guerra e Paz; Gustavo Capanema Palace in Rio de Janeiro; 1952–56) was a mural created when the United Nations asked Brazil to donate a work of art. Portinari created two murals to show war, agony, fear and pain that showed how the people suffered and were affected during the war. His use of blue hues in War created a contrast between the lighter yellows in Peace. The second was meant to express peace and happiness. Bento Antonio in his book Portinari, describes this work as, “a sort of innocent vision of paradise.” With this mural, he also meant to connect different racial groups and show peace among the variety of individuals. There was a large variety of ethnicities that lived in Brazil at this time. His works were meant to create a bridge between the multicultural individuals. This work is located in the United Nations General Assembly Building in New York which was created in remembrance to World War II and its horrors. It was meant to resemble something that should never occur again. Here, visitors come witnessing an epitome of war and leave realizing that peace is indeed attainable.[15] Guerra e Paz is the synthesis of an entire life committed to human beings. His painting, like his militant political views, spoke out against injustice, violence and misery in the world, according to the artist's son, João Candido Portinari.[16]

In the Hispanic Foundation of the Library of Congress, Washington D.C. are located four murals that Portinari did in 1941 depicting the struggles of the Hispanic Americans. Discovery of the Land, Entry into the Forest, Teaching of the Indians, and Discovery of Gold are all meant to represent the coming of the Spaniards and Portuguese to America and took him two months to complete with the help of his brother Luiz. The Discovery of the Land is meant to show common sailors that sailed the boats. Entry in the Forest is the “reminiscent of frescoes” where he also doesn't fail to capture his style of enlarging the figures’ arms and legs to show their strength. In the Teaching of the Indians, Portinari tries to create a scene of a priest or Spanish “Jesuit father” with Indians and obvious unity. Also the presence of the red Brazilian soil. The last mural, Discovery of Gold the artist chooses to paint just a single boat and specific people to represent that they had found gold. The Brazilian government paid for Portinari to travel to Washington to create the murals and represent their country.[17]

Legacy

[edit]Portinari once said, “I am the Son of the Red Earth. I decided to paint the Brazilian reality, naked and crude as it is.”[18] Life in Brazil wasn't easy for Portinari, especially considering he was never wealthy, but his desire to show proof of this reality is evident in all his artworks. Poor housing, inadequate nutrition, no education, little or no healthcare access and various diseases created desperate situations for the Brazilian people who struggled to survive. This led to Portinari's desire to raise global awareness of the human pain which he tried to depict in almost every painting.

Portinari also greatly affected the future Brazilian generation of artists, musicians, poets and composers. Having vastly traveled Europe, studying their art, their technique and styles, he came back to Brazil hoping to create his personal method and interpret his own style. Instead of continuing to imitate the European appearance, Portinari painted what he experienced and his life. Portinari's works urged emerging artists to pursue their own, unique style particular to their lives, experiences and reality in their country. This is also another reason blues, reds, and oranges were so commonly used in his art; the colors of his homeland.[19]

Projeto Portinari, begun in 1979 is dedicated to Candido Portinari by his son Joao Candido to revive his works, make them more known and preserve the history. Not only was his son able to locate more than 5,000 paintings, he also found thousands of drawings, sketches, and documents related to Portinari's life and travels and interactions.[2] The Catalogue Raisonné of Portinari's complete works was published in 2004. It was the first Raisonné covering the complete works of a Latin American painter. “Projeto Portinari” also curated the first retrospective exhibition of Portinari's oeuvre, at the “Museu de Arte de São Paulo – MASP”, in 1997.

Nicolás Guillén's and Horacio Salinas's ‘Un son para Portinari’, famously performed by Mercedes Sosa, is dedicated to the artist. Candido Portinari name continues to be seen today. Rodovia Candido Portinari is a State highway located in Brazil in São Paulo.[citation needed]

Works

[edit]Paintings and murals

- 1932 Fishes with Lemon

- 1933 Morro or Hill. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art

- 1934 Coffee Growers

- 1934 Seated Women

- 1934 Dispossessed

- 1934 The Mestizo

- 1935 Coffee. Collection of the National Museum of Fine Arts- Second Honorable Mention, Rio De Janeiro

- 1936 Woman and Child

- 1938 Cocoa

- 1938 Women Tilling

- 1938 Composition with Figures

- 1939 Family

- 1939 Earthquake

- 1939 Tobacco

- 1940 Carcass

- 1940 Surrealist Landscape

- 1940 Oxen and Landscape

- 1941 Discovery of the Land. Hispanic Foundation, Library of Congress; Washington D.C.

- 1941 Entry into the Forest. Hispanic Foundation, Library of Congress; Washington D.C.

- 1941 Teaching of the Indians. Hispanic Foundation, Library of Congress; Washington D.C.

- 1941 Discovery of Gold. Hispanic Foundation, Library of Congress; Washington D.C.

- 1952 War. United Nations General Assembly building; New York

- 1952. Peace. United Nations General Assembly building;New York

Further reading

[edit]- Giunta, Andrea, ed. Cândido Portinari y el sentido social del arte. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI 2005.

- Vitureira, Cipriano S. Portinari en Montevideo. Montevideo: Alfar 1949.

- Candido Portinari (2018). Poemas de Portinari [Poems by Portinari] (PDF) (in Brazilian Portuguese) (3 ed.). Funarte. p. 192. ISBN 978-85-7507-198-4. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Library of Congress (1943). Murals by Candido Portinari. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e "Portal Portinari".

- ^ Bento, Antonio (1982). Portinari. Leo Christiano Editorial.

- ^ ABREU, Alzira Alves de. Dicionário Histórico-Biográfico Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro; Fundação Getúlio Vargas; 2004.

- ^ Candido Portinari[1]Galeria de Arte André.

- ^ Kaufman, James C (2014). Creativity and Mental Illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 9781107021693.

- ^ "Image: lavrador-de-cafe.jpg, (819 × 1030 px)". ritualcafe.files.wordpress.com. 2005-07-18. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- ^ MacSwan, Angus (2007-12-21). "Security questioned in Picasso theft in Brazil". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2007-12-30.

- ^ Winter, Michael (2008-01-08). "Stolen Picasso, Portinari recovered in Brazil". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2008-04-12.

- ^ "Portinari Murals at Library of Congress". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^ Bento, Antônio. Portinari. Rio de Janeiro: Léo Christiano Editorial, 1982.

- ^ Barnitz, Jacqueline, and Patrick Frank. Twentieth-century art of Latin America. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015.

- ^ a b Museum of Modern Art (1940). Portinari of Brazil. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

- ^ Ades, Dawns. Art in Latin America: The Modern Era, 1820-1980.

- ^ "THE SECOND UNVEILING OF "WAR AND PEACE"". Archived from the original on 2020-08-14. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ^ Alisson, Elton. "Portinari's War and Peace are shown for the first time in São Paulo".

- ^ "Hispanic Reading Room". Library of Congress.

- ^ Breedlove, Byron; Sorvillo, Frank J. (2016). "I Am a Son of the Red Earth". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (8): 1524–1525. doi:10.3201/eid2208.ac2208. PMC 4982151.

- ^ Hoge, Warren; Times, Special to the New York (1983-05-30). "BRAZIL GATHERS ARCHIVE ON ITS PAINTER, PORTINARI". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-12-06.