Knurling

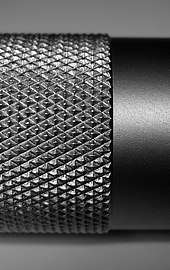

Knurling is a manufacturing process, typically conducted on a lathe, whereby a pattern of straight, angled or crossed lines is rolled into the material. Knurling can also refer to material that has a knurled pattern.[1]

Etymology

[edit]The terms knurl and knurled are from an earlier knur ‘knot in wood’ and the diminutive -le, from Middle English knaur or knarre ‘knot in wood; twisted rock; crag’.[2] This descends from Old English cnearra but the vowel in Middle English may have been influenced by Old Norse knǫrr ‘merchant ship’ which was known as cnearr in Old English.[citation needed] The modern gnarl is a back-formation of gnarled which itself is first attested in Shakespeare's works and is apparently a variant of knurled.[3]

Uses

[edit]

Knurling produces indentations on a part of a workpiece, allowing hands or fingers to get a better grip on the knurled object than would be provided by the original smooth surface. Occasionally, the knurled pattern is a series of straight ridges or a helix of "straight" ridges rather than the more-usual criss-cross pattern.

Knurling may also be used as a repair method: because a rolled-in knurled surface has raised areas surrounding the depressed areas, these raised areas can make up for wear on the part. In the days when labor was cheap and parts expensive, this repair method was feasible on pistons of internal combustion engines, where the skirt of a worn piston was expanded to the nominal size using a knurling process. As auto parts have become less expensive, knurling has become less prevalent than it once was, and is specifically discouraged by the builders of performance engines.[4]

Knurling can also be used when a component will be assembled into a low-precision component, for example a metal pin into a plastic molding. The outer surface of the metal pin is knurled so that the raised detail "bites" into the plastic irrespective of whether the size of the hole in the plastic closely matches the diameter of the pin.

Tool handles, mechanical pencils, the grips of pistols, barbell bars, the clamping surface of a motorcycle handlebar and the control knobs on electronic equipment are frequently knurled. Knurling is also used on the grips of darts[5] and on the footpegs of BMX bicycles. Knurling is also found in many surgical instruments, where it is used for instrument identification, and for its ease of being brushed clean.

Process

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

More common than knurl cutting, knurl rolling is usually accomplished using one or more very hard rollers that contain the reverse of the pattern to be imposed. It is possible for a "straight" knurl (not criss-crossed) to be pressed with a single roller, however the material needs to be supported adequately to avoid deformation. A criss-cross pattern can be accomplished using any of:

- A single roller that contains the reverse of the complete desired pattern. These are available to form either "male" or "female" patterns,

- A left-handed straight roller followed by a right-handed straight roller (or vice versa), or

- One or more left-handed rollers used simultaneously with one or more right-handed rollers.

Use stock with a circumference that's a multiple of the circular pitch, or stock with a diameter of the circular pitch over π. Blank diameter is critical to quality knurling. The wrong blank diameter can cause the knurl(s) to double track, giving a pattern finer than the knurl was designed to produce, one that is generally unsatisfactory. Picking the correct stock diameter is very similar to having two gears of the same diametrical pitch that fit together. Every time you add a tooth, the diameter increases by a discrete amount. There are no in-between diameters that work correctly. The same is true of knurls and the blank to be knurled, though fortunately knurls do tolerate a certain amount of error before problems occur.[6][7] The integer number of knurls for any given diameter typically varies by three repetitions from the bottom to the top of the pattern. By comparison, for cut knurls, the spacing of the cuts is not preset and can be adjusted to allow an integral number of patterns around the workpiece no matter what the diameter of the workpiece.

Hand knurling tools are available. These resemble pipecutters but contain knurling wheels rather than cutting wheels. Usually, three wheels are carried by the tool: two left-handed wheels and one right-handed wheel or vice versa.

Cut knurling often employs automatic feed. The tooling for cut knurling resembles that for rolled knurling, with the exception that the knurls have sharp edges and are presented to the work at an angle allowing the sharp edges to cut the work. Angled, diamond and straight knurling are all supported by cut knurling.[8] It is impossible to cut knurling "Like extremely coarse pitch threads" both because lathe gear trains will not support such longitudinal speeds and because reasonable cutting speeds would be impossible to achieve.

Types

[edit]- Annular rings

- Frequently used when the mating part is plastic. Rings allow for easy mating but ridges make it difficult to pull the components apart.

- Linear knurl

- Used with mating plastic pieces, the linear knurl allows greater torsion between components.

- Diamond knurl

- A hybrid of annular rings and linear knurling in which a diamond shape is formed. It is used to provide better grip on components, and is the most common type used on everyday objects.

- Straight knurling

Source:[9]

References

[edit]- ^ "Knurls & Knurling" (PDF). Reed Machinery. p. 3. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

Knurling is obtained by displacement of the material when the knurl is pressed against the surface of a rotating work blank.

- ^ Barnhart 1988, p. 569.

- ^ Barnhart 1988, p. 438.

- ^ Monroe, Tom. "Engine Rebuilder's Handbook". HPBooks, New York, 1996. Page 48.

- ^ How It's Made - Darts (knurling wheels at 2:50)

- ^ "Conrads Easy Knurling Method".

- ^ Knurling Tools doriantool.com

- ^ Cut-Knurling tools

- ^ "2. Design and types of knurling tools".

Bibliography

[edit]- Barnhart, Robert K., ed. (1988). Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology (1st ed.). Bronx, New York: The H. W. Wilson Company. p. 569. ISBN 0824207459.