Claude Fauchet (historian)

Claude Fauchet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 3 July 1530 Paris |

| Died | January 1602 Paris |

| Occupation | President of the Cour des monnaies, historian, antiquarian, romance philologist, medievalist, translator |

| Nationality | French |

| Literary movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Notable works | Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poesie françoise (1581) |

| Signature | |

Claude Fauchet (French pronunciation: [klod foʃɛ]; 3 July 1530 – January 1602) was a sixteenth-century French historian, antiquary, and pioneering romance philologist.[1] Fauchet published the earliest printed work of literary history in a vernacular language in Europe, the Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poësie françoise (1581).[2][3][4][5] He was a high-ranking official in the governments of Charles IX, Henri III, and Henri IV, serving as the president of the Cour des monnaies.

Early life

[edit]He was born in Paris, to Nicole Fauchet, procureur au Châtelet, and Geneviève Audrey, granddaughter of Jacques III De Thou. His mother was also connected through her daughter from an earlier marriage to the Godefroy family.[2] Fauchet was thus closely connected by birth to the world of the Paris Parlement.

Fauchet studied at the University of Paris before taking his degree in civil law at the University of Orléans in 1550.[2] He subsequently travelled through northern Italy, visiting Rome and also Venice, where he made the acquaintance of the humanist Sperone Speroni.[2]

Upon his return to Paris, Fauchet composed a series of short essays based on his wide reading in medieval French literature, much of which had not yet been printed and was only accessible in manuscript. He entitled this collection Les Veilles ou observations de plusieurs choses dinnes de memoire en la lecture d'aucuns autheurs françois par C.F.P., dated to 1555.The Veilles (French for 'vigils') are a literary miscellany in the tradition of Aulus Gellius's Attic Nights.[2][6]

The author's manuscript of this miscellany still exists; it was never printed in full in Fauchet's lifetime, though he would recycle parts of it in his later printed works on the history of French poetry and French magistratures.

Later life and the Recueil of 1581

[edit]Fauchet was eventually made second president of the Cour des monnaies (29 March 1569), and subsequently rose to the rank of premier président in 1581. He held this office until 1599.[2] Among his friends and colleagues are to be counted Étienne Pasquier, Antoine Loisel, Henri de Mesmes, Louis Le Caron, Jean-Antoine de Baïf, Jacopo Corbinelli, Gian Vincenzo Pinelli, Filippo Pigafetta, Sperone Speroni, and many other learned and erudite characters of the sixteenth century.[7][1]

Fauchet's most important published work is his history of the French language and its poetry, the Recueil de l’origine de la langue et poësie françoise (1581). The book is in two parts. The first part consists of a history of the development of the French language, out of a mixture of Gallo-Roman with Frankish elements.[8] The second part of the Recueil is an anthology of 127 French poets living prior to 1300. Fauchet's theorising about language formation in the first book has been praised as ahead of its time,[9] and throughout he demonstrates a profound knowledge of contemporary linguistic theory, as well as engaging with earlier and less frequently cited traditions of linguistic theory such as Dante's De vulgari eloquentia.[10] The Recueil was much used in the following two centuries by literary historians and antiquarians curious about medieval French literature.[11]

During the Wars of Religion, as a member of the government of Henri III, Fauchet was forced to flee Paris in 1589 and could not return until 18 April 1594, now in the service of the new king, Henri IV. During this absence, Fauchet's Paris residence was sacked, resulting in the loss of his library: more than two thousand volumes, by his own account, many of which were manuscripts.[12][13] Many medieval manuscripts once belonging to Fauchet now reside in the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the Bibllioteca Apostolica Vaticana in the Vatican,[14][15][13][16] while some are scattered across Europe's libraries (Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris; the British Library; Berlin State Library; Dijon Public Library; National Library of Sweden; Burgerbibliothek of Berne; Biblioteca Ambrosiana) and still many others remain unaccounted for.[14]

The wars left Fauchet poor, and in 1599 he had to sell his office in the Cour des monnaies. Fauchet published most of his print works during this period, from 1599 to his death in 1602. Henri IV, said to have been amused with an epigram written by Fauchet, supposedly pensioned him with the title of historiographer of France, but there is no official record of this.[17] He died in Paris.

Fauchet has the reputation of being an impartial and scrupulously accurate writer, and in his works are to be found important facts not easily accessible elsewhere. His works taken together form a history of antiquities of Gaul and of Merovingian and Carolingian France (1579, 1599, 1601, 1602), of the dignities and magistrates of France (1600), of the origin of the French language and poetry (1581), and of the liberties of the Gallican church. A collected edition in a single massive volume was published in 1610.[18][19]

Fauchet read widely throughout his life among the key authors of Old and Middle French literature, including chroniclers and historians such as Jean Froissart, Enguerrand de Monstrelet, and Philippe de Commynes; and poets, such as Gace de la Buigne, Guillaume de Lorris, Jean de Meun, Huon de Méry, Hugues de Berzé, and Chrétien de Troyes. Fauchet was also the first person to use the name 'Marie de France' to refer to the Anglo-Norman writer of the Lais.[20]

Translation of Tacitus

[edit]Alongside his work as a historian and as a civil servant, Fauchet was also the first person to translate the complete works of Tacitus into French.[2][21] A partial translation of the Annals (books XI-XVI) appeared anonymously for the first time alongside a translation of Annals, I-V, by Estienne de la Planche in an edition printed for Abel l'Angelier in 1581.[22] The next year, l'Angelier brought out Fauchet's complete translation of the works of Tacitus (the Annals, Histories, Germania, and Agricola, but minus the Dialogue on Orators), which was reprinted in 1584.[23] A translation of the Dialogue on Orators was brought out in 1585.[24] While these translations were not openly published under Fauchet's name until the posthumous edition of 1612,[25] the attribution is not in question.[26]

Fauchet's name

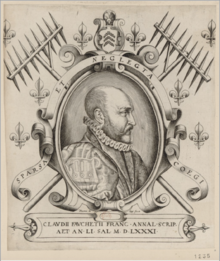

[edit]Fauchet enjoyed punning on the etymology of his surname and on its symbolism for his activity as an antiquarian.[8] In French, a 'fauchet' is an old-fashioned hay rake, used for gathering in the cut grass. Fauchet's personal motto was 'sparsa et neglecta coegi', i.e. 'I have gathered scattered and neglected things', a reference to the obscure and ancient texts he collected (or 'raked in') and used for his historical research. A Latin motto which appears beneath his portrait of 1599 reads 'Falchetus Francis sparsa & Neglecta coëgi / Lilia queis varium hoc continuatur opus.' (I Fauchet have gathered for the French scattered and neglected / lilies with which this varied work is made). In the Recueil of 1581, Fauchet proudly writes, 'suivant ma devise, j'ai recueilli ce qui estoit espars et delaissé: ou si bien caché, qu'il eust esté malaisé de le trouver sans grand travail' ('following my motto, I have gathered what was scattered and abandoned: or so well hidden, that it would have been difficult to find without much exertion').[8] Fauchet's activity as a collector of medieval manuscripts played a crucial role in the transmission of medieval French literature to the modern age.[27][28]

Works

[edit]- 1555, Veilles ou observations de plusieurs choses dinnes de memoire en la lecture d'aucuns autheurs françois, BnF MS fr. 24726, ff.1–52

- 1579, Recueil des antiquitez gauloises et françoises, Paris: J. Du Puys

- 1581, Les Annales de P. Cornile Tacite, (books XI-XVI), Paris: Abel l'Angelier

- 1581, Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poesie françoise, ryme et romans. Plus les noms et sommaire des oeuvres de CXXVII. poetes François, vivans avant l’an M. CCC. Paris: Mamert Patisson

- 1582, Les Œuvres de C. Cornilius Tacitus, Chevalier Romain, Paris: Abel l'Angelier (first printed partially in 1581; reprinted in 1584)

- 1585, Dialogue des orateurs, Paris: Abel l'Angelier

- 1599, Les Antiquitez gauloises et françoises augmentées de trois livres contenans les choses advenues en Gaule et en France jusques en l'an 751 de Jésus-Christ,

- 1600, Origines des dignitez et magistrats de France, Paris: J. Périer (originally written in 1584, at the request of Henri III)

- 1600, Origine des chevaliers, armoiries et héraux, ensemble de l'ordonnance, armes et instruments desquels les François ont anciennement usé en leurs guerres, Paris: J. Périer

- 1601, Fleur de la maison de Charlemaigne, qui est la continuation des Antiquitez françoises, contenant les faits de Pépin et ses successeurs depuis l'an 751 jusques à l'an 840, Paris: J. Périer

- 1602, Declin de la maison de Charlemaigne, faisant la suitte des Antiquitez françoises, contenant les faits de Charles le Chauve et ses successeurs, depuis l'an 840 jusques à l'an 987, Paris: J. Périer

- 1610, Les Œuvres de feu M. Claude Fauchet premier president en la cour des monnoyes, Paris: Jean de Heuqueville

Opuscules and manuscripts

[edit]These three short treatises were only printed for the first time in the posthumous Œuvres[19] of 1610:

- Traité des Privileges et Libertez de l'Eglise gallicane

- Pour le couronnement du roi Henri IV

- Armes et Bastons des Chevaliers (lettre à Monsieur de Galoup sieur des Chastoil en Aix)

The following manuscripts contain numerous unpublished writings by Fauchet on a variety of different topics:

- Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS fr. 24726 (available on Gallica)

- Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, MS Reg.lat.734

- Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, MS Ottob.2537

See also

[edit]- The Pléiade

- Guillaume Budé

- Pierre Pithou

- Papire Masson

- Paul Pétau

- La Curne de Sainte-Palaye

- Medieval French literature

- John Leland

- John Weever

- William Camden

- Jan Dousa

- Charles de Pougens

- Laurence Nowell

- Janet G. Scott

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Espiner-Scott, Janet Girvan (1940). "Claude Fauchet and Romance Study". The Modern Language Review. 35 (2): 173–184. doi:10.2307/3717326. JSTOR 3717326.

- ^ a b c d e f g Espiner-Scott, Janet Girvan (1938). Claude Fauchet: Sa vie, son œuvre. Paris: E. Droz.

- ^ Saintsbury, George (1900–1904). History of Criticism. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Blackwood. p. 135.

- ^ Darmsteter, Arsène; Hatzfeld, Adolphe (1883). Le Seizième siècle en France: Tableau de la littérature et de la langue. Paris: Ch. Delagrave. p. 75.

- ^ Bruder, Anton (2018). "Linguistic and Material Counterculturalism in the French Renaissance: Claude Fauchet's Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poësie françoise (1581)". Early Modern French Studies. 40 (2): 117–132. doi:10.1080/20563035.2018.1539372. S2CID 165220207.

- ^ Coulombel, Arnaud (2018). "Langue, Poésie et Histoire: Les Veilles (1555) de Claude Fauchet et la défense d'une tradition nationale". Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes. 35: 474–494.

- ^ Espiner-Scott, Janet Girvan (1936). "Note sur le cercle de Henri de Mesmes et sur son influence". Mélanges offerts à M. Abel Lefranc par ses élèves et ses amis. Paris: E. Droz.

- ^ a b c Fauchet, Claude (1581). Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poësie françoise, rymes et romans. Paris: Mamert Pattison. pp. livre I.

- ^ Dubois, Claude-Gilbert (1970). Mythe et langage au XVIe siècle. Bordeaux: Ducros.

- ^ Fauchet, Claude (1938). Espiner-Scott, Janet Girvan (ed.). Recueil de l'origine de la langue et poésie françoise: rymes et romans. Paris: E. Droz.

- ^ Edelman, Nathan (1946). Attitudes of Seventeenth-Century France toward the Middle Ages. New York: King's Crown Press.

- ^ Fauchet, Claude (1599). Les Antiquitez gauloises et françoises. Paris: Jeremie Perier. pp. ā iiii + 4.

- ^ a b Holmes, Urban T.; Radoff, Maurice L. (1929). "Claude Fauchet and his Library". Proceedings of the Modern Language Association. 44 (1): 229–242. doi:10.2307/457676. JSTOR 457676.

- ^ a b Espiner-Scott, Janet Girvan (1938). Documents concernant la vie et l'œuvre de Claude Fauchet. Paris: E. Droz. pp. 203–230.

- ^ Bisson, Sidney Walter (1935). "Claude Fauchet's Manuscripts". The Modern Language Review. 30 (3): 311–323. doi:10.2307/3715309. JSTOR 3715309.

- ^ Dillay, Madeleine (1932). "Quelques données bio-bibliographiques sur Claude Fauchet (1530–1602)". Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. 33: 35–82.

- ^ Simonnet, Jules (1863). "Le président Fauchet, sa vie et ses ouvrages". Revue historique de droit français et étrange. 9: 425–470.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b Fauchet, Claude (1610). Les Œuvres de feu M. Claude Fauchet, premier president en la cour des monnoyes. Reveues et corrigees en ceste derniere edition, suppleées & augmentées sur la copie, memoires & papiers de l'Autheur, de plusieurs passages & additions en divers endroits. Paris: Jean de Heuqueville.

- ^ Burgess, Glyn Sheridan; Busby, Keith (1986). The Lais of Marie de France. Penguin. p. 11.

- ^ Bermejo, Saúl Martínez (2010). Translating Tacitus: The Reception of Tacitus's Works in the Vernacular Languages of Europe, 16th–17th centuries. Pisa: PLUS-Pisa University Press. p. 22.

- ^ Tacitus, C. Cornelius (1581). Les Annales de P. Cornile Tacite. (trans. Estienne de la Plance and [Claude Fauchet]). Paris: Abel l'Angelier.

- ^ Tacitus, C. Cornelius (1582). Les Œuvres de C. Cornilius Tacitus, chevalier romain. (trans. [Claude Fauchet]). Paris: Abel l'Angelier.

- ^ Tacitus, C. Cornelius (1585). Dialogue des orateurs. (trans. [Claude Fauchet]). Paris: Abel l'Angelier.

- ^ Tacitus, C. Cornelius (1612). C. Cornelii Taciti opera latina cum versione gallica. (trans. Estienne de la Plance and Claude Fauchet). Frankfurt: Nicolaus Hoffmann.

- ^ Lombart, Nicolas (2015). "Fauchet, Claude". Écrivains juristes et juristes écrivains du Moyen Âge au siècle des Lumières. Paris: Classiques Garnier: 455–464.

- ^ Haines, John (2005). Eight Centuries of Troubadours and Trouvères: The Changing Identity of Medieval Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. chapter 2.

- ^ Clérico, Geneviève (1991). "Claude Fauchet et la littérature médiévale des origines". La littérature et ses avatars: discrédits, déformations et réhabilitations dans l'histoire de la littérature: actes des cinquièmes Journées rémoises, 23–27 novembre 1989. Paris: Éditions aux amateurs de livres.

References

[edit]- Janet Girvan Espiner-Scott, Claude Fauchet: Sa vie, son œuvre, Paris: E. Droz, 1938. Espiner-Scott's works form the foundation of all modern research into Fauchet; this volume remains the best and most comprehensive study of Fauchet's life and works to date.

- Urban T. Holmes and Maurice L. Radoff "Claude Fauchet and His Library" PMLA 44.1 (March 1929), pp. 229–242. Brief details of his life, lists of published works, of volumes identified as from his library and works cited by Fauchet.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Fauchet, Claude". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 205.