Otto Dix

Otto Dix | |

|---|---|

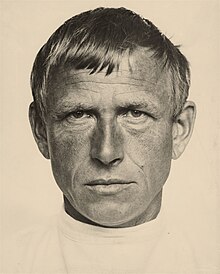

Otto Dix (photograph by Hugo Erfurth, c. 1933) | |

| Born | Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix 2 December 1891 |

| Died | 25 July 1969 (aged 77) Singen, Baden-Württemberg, West Germany |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking |

| Movement | Expressionism, New objectivity, Dada |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Iron Cross, 2nd class 1918 |

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix (German: [ˈvɪlhɛlm ˈhaɪnʁɪç ˈʔɔtoː ˈdɪks]; 2 December 1891 – 25 July 1969)[1] was a German painter and printmaker, noted for his ruthless and harshly realistic depictions of German society during the Weimar Republic and the brutality of war. Along with George Grosz and Max Beckmann, he is widely considered one of the most important artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit.[2]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Otto Dix was born in Untermhaus, Germany, now a part of the city of Gera, Thuringia. The eldest son of Franz Dix, an iron foundry worker, and Louise, a seamstress[3] who had written poetry in her youth, he was exposed to art from an early age.[4] The hours he spent in the studio of his cousin, Fritz Amann, who was a painter, were decisive in forming young Otto's ambition to be an artist; he received additional encouragement from his primary school teacher.[4] Between 1906 and 1910, he served an apprenticeship with painter Carl Senff, and began painting his first landscapes. In 1910, he entered the Kunstgewerbeschule in Dresden, now the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, where Richard Guhr was among his teachers. At that time the school was not a school for the fine arts but rather an academy that concentrated on applied arts and crafts.[5]

The majority of Dix's early works concentrated on landscapes and portraits which were done in a stylized realism that later shifted to expressionism.[6]

World War I service

[edit]

When the First World War erupted, Dix volunteered for the German Army. He was assigned to a field artillery regiment in Dresden.[7] In the autumn of 1915 he was assigned as a non-commissioned officer of a machine-gun unit on the Western front and took part in the Battle of the Somme. In November 1917, his unit was transferred to the Eastern front until the end of hostilities with Russia, and in February 1918 he was stationed in Flanders. Back on the western front, he fought in the German spring offensive. He earned the Iron Cross, 2nd class, and reached the rank of Vizefeldwebel. In August of that year he was wounded in the neck, and shortly after he took pilot training lessons.

He took part in an anti-aircraft course in Tongern, was promoted to Vizefeldwebel and after passing the medical tests transferred to Aviation Replacement Unit Schneidemühl in Posen. He was discharged from service on 22 December 1918 and was home for Christmas.[8]

Dix was profoundly affected by the sights of the war, and later described a recurring nightmare in which he crawled through destroyed houses. He represented his traumatic experiences in many subsequent works, including a portfolio of fifty etchings called Der Krieg, published in 1924.[9] Subsequently, he referred to the war again in The War Triptych, painted from 1929 to 1932.

Post-war artwork

[edit]At the end of 1918 Dix returned to Gera, but the next year he moved to Dresden, where he studied at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste. He became a founder of the Dresden Secession group in 1919, during a period when his work was passing through an expressionist phase.[10] In 1920, he met George Grosz and, influenced by Dada, began incorporating collage elements into his works, some of which he exhibited in the first Dada Fair in Berlin. He also participated in the German Expressionists exhibition in Darmstadt that year.[7]

He met metalsmith Martha Koch in 1921, and they married in 1923. They had three children together. She was a frequent subject of his portraits.[11]

In 1924, he joined the Berlin Secession; by this time he was developing an increasingly realistic style of painting that used thin glazes of oil paint over a tempera underpainting, in the manner of the old masters.[12] His 1923 painting The Trench, which depicted dismembered and decomposed bodies of soldiers after a battle, caused such a furor that the Wallraf-Richartz Museum hid the painting behind a curtain. In 1925 the then-mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, canceled the purchase of the painting and forced the director of the museum to resign.

Dix was a contributor to the Neue Sachlichkeit exhibition in Mannheim in 1925, which featured works by George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Karl Hubbuch, Rudolf Schlichter, Georg Scholz and many others. Dix's work, like that of Grosz—his friend and fellow veteran—was extremely critical of contemporary German society and often dwelled on the act of Lustmord, or sexualized murder. He drew attention to the bleaker side of life, unsparingly depicting prostitution, violence, old age, and death.

In one of his few statements, published in 1927, Dix declared, "The object is primary and the form is shaped by the object."[13]

Among his most famous paintings are Sailor and Girl (1925), used as the cover of Philip Roth's 1995 novel Sabbath's Theater, the triptych Metropolis (1928), a scornful portrayal of decadence and depravity in Germany's Weimar Republic,[14] where nonstop revelry was a way to deal with the wartime defeat and financial catastrophe,[15] and the startling Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden (1926). His depictions of legless and disfigured veterans—a common sight on Berlin's streets in the 1920s—unveil the ugly side of war and illustrate their forgotten status within contemporary German society, a concept also developed in Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front.

Although frequently recognized as a painter, Dix drew self-portraits and portraits of others using the medium of silverpoint on prepared paper. "Old Woman," drawn in 1932, was exhibited with old-master drawings.[16]

The Nazis and World War II

[edit]The Nazi-affiliated Deutsche Kunstgesellschaft Dresden [The German Art Society Dresden] had defined Dix as one of Germany's most 'degenerate' artists long before the Nazis' takeover of power in January 1933. For example, when Metropolis was exhibited in Dresden for the first time in 1928, one of the German Art Society's founding members and most prominent writer Bettina Feistel-Rohmeder pilloried both Dix personally and the depiction of German society that Metropolis offered, in the Society's art bulletin, the Deutsche Kunstkorrespondenz [German Art Correspondence].[17] In April 1933, Richard Müller, who with Feistel-Rohmeder had founded the Deutsche Kunstgesellschaft Dresden, sacked Dix from his post as a professor of painting at the Dresden Academy, on a directive from Saxony's Reichskommissar Manfred von Killinger. Dix later moved to Lake Constance in the southwest of Germany. Dix's paintings The Trench and War Cripples were exhibited in the state-sponsored Munich 1937 exhibition of degenerate art, Entartete Kunst. War Cripples was later burned.[18] The Trench was long thought to have been destroyed too, but there are indications the work survived until at least 1940. Its later whereabouts are unknown; it may have been looted during the confusion at the end of the war. It has been called 'perhaps the most famous picture in post-war Europe ... a masterpiece of unspeakable horror.[19]

Dix, like all other practising artists, was forced to join the Nazi government's Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of Goebbels' Cultural Ministry (Reichskulturkammer). Membership was mandatory for all artists in the Reich. Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes. He still painted an occasional allegorical painting that criticized Nazi ideals.[20] His paintings that were considered "degenerate" were discovered in 2012 among the 1500+ paintings hidden away by the son of Hitler's looted-art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt.[21][22][23]

In 1939 he was arrested on the trumped-up charge of being involved in a plot against Hitler (see Georg Elser), but was later released.

During World War II, Dix was conscripted into the Volkssturm. He was captured by French troops at the end of the war and released in February 1946.

Later life and death

[edit]

Dix eventually returned to Dresden and remained there until 1966. After the war most of his paintings were religious allegories or depictions of post-war suffering, including his 1948 Ecce homo with self-likeness behind barbed wire. In this period, Dix gained recognition in both parts of the then-divided Germany. In 1959 he was awarded the Grand Merit Cross of the Federal Republic of Germany (Großes Verdienstkreuz) and in 1950, he was unsuccessfully nominated for the National Prize of the GDR. He received the Lichtwark Prize in Hamburg and the Martin Andersen Nexo Art Prize in Dresden to mark his 75th birthday in 1967. Dix was made an honorary citizen of Gera. Also in 1967 he received the Hans Thoma Prize and in 1968 the Rembrandt Prize of the Goethe Foundation in Salzburg.

Dix died on 25 July 1969 after a second stroke in Singen am Hohentwiel. He is buried at Hemmenhofen on Lake Constance.

Dix had three children: a daughter Nelly; and two sons, Ursus and Jan.

Otto Dix House Museums

[edit]

The Otto-Dix-Haus was opened in 1991, at the 100th anniversary of Dix's birth, in the 18th-century house where he was born and grew up, at Mohrenplatz 4 in the city of Gera, as a museum and art gallery. It is managed by the city administration.

As well as providing access to the rooms Dix lived in, it houses a permanent collection of 400 of his works on paper and paintings. Visitors can see examples of his childhood sketch books, watercolours and drawings from the 1920s and 1930s, and lithographs. The collection also includes 48 postcards he sent from the front during World War I.[24] The gallery also regularly hosts temporary exhibitions.

The building was affected by a flood in June 2013. In order to repair the underlying damage, the museum was closed in January 2016, and re-opened in December 2016 following restoration.[25]

The Museum Haus Dix was inaugurated in 2013 in the house where the artist lived with his family and where he worked from 1936 to 1969, in Hemmenhofen, south Germany.[26]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Otto Dix | German artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Tate. "Five things to know: Otto Dix – List". Tate. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ York, Neue Galerie New. "Neue Galerie New York". neuegalerie.org. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ a b Karcher 1988, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Intransigent Realism: Otto Dix between the World Wars. Ed. Olaf Peters. (New York: Prestel, 2010) 14.

- ^ Fritz Löffler, Otto Dix Life and Work (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 1982) p. 14.

- ^ a b Karcher 1988, p. 251.

- ^ Norbert Wolf, Uta Grosenick (2004), Expressionism, Taschen, p. 34. ISBN 3-8228-2126-8.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (14 May 2014). "The first world war in German art: Otto Dix's first-hand visions of horror". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Michalski, Sergiusz (2003). Neue Sachlichkeit: Malerei, Graphik und Photographie in Deutschland 1919–1933. Taschen. ISBN 9783822823729.

- ^ Rewald, Sabine (2006). Glitter and Doom: German Portraits from the 1920s. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 249. ISBN 9781588392008. Retrieved 20 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Karcher 1988, p. 252.

- ^ Ashton, Dore (April 2010). "Otto Dix Neue Galerie". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ Karcher 1988, pp. 162, 193.

- ^ Exhibition of "Cabaret" Era Opens at Met Museum, ARTINFO, 14 November 2006, retrieved 23 April 2008

- ^ Sell, S. and Chapman, H. Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns. p. 230. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ. 2015.

- ^ Murray, Ann (2023). Otto Dix and the Memorialisation of World War I in German Visual Culture, 1914-1936 (1st ed.). London: Bloomsbury. pp. 124–146. ISBN 9781350354647. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ "Khan Academy". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Tate Gallery". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ Conzelmann, 1959, p. 50.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (2013) In a Rediscovered Trove of Art, a Triumph Over the Nazis' Will in The New York Times (Accessed: 16 January 2017).

- ^ "Photo Gallery: Munich Nazi Art Stash Revealed". Der Spiegel. 17 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ ""Trésor nazi": la petite-fille d'Otto Dix accuse Berlin – Nazi Treasure – Otto Dix's Granddaughter accuses Berlin". L'Express. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Kunstsammlung Gera / Otto-Dix-Haus (in German) (Accessed: 16 January 2017).

- ^ Hilbert, Marcel (2016) Hochwasserschäden werden repariert: Otto-Dix-Haus in Gera seit 4. Januar geschlossen (Accessed: 16 January 2017).

- ^ "Museum Haus Dix at the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart Official Website (German)".

References

[edit]- Conzelmann, O., Otto Dix (Hannover: Fackelträger-Verlag, 1959).

- Hinz, Berthold (1979). Art in the Third Reich, trans. Robert and Rita Kimber. Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag. ISBN 0-394-41640-6.

- Karcher, Eva (1988). Otto Dix 1891–1969: His Life and Works. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen. OCLC 21265198

- Michalski, Sergiusz (1994). New Objectivity. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-9650-0.

- Schmied, Wieland (1978). Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism of the Twenties. London: Arts Council of Great Britain. ISBN 0-7287-0184-7.

- Murray, Ann (2023). Otto Dix and the Memorialization of World War I in German Visual Culture, 1914-1936. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781350354647.

External links

[edit]- 1891 births

- 1969 deaths

- People from Gera

- People from the Principality of Reuss-Gera

- 20th-century German painters

- 20th-century German male artists

- German male painters

- German war artists

- German modern painters

- Dada

- German Expressionist painters

- German Esperantists

- Volkssturm personnel

- Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 2nd class

- Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- World War II artists

- World War I artists

- Academic staff of the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts

- German Army personnel of World War I

- German prisoners of war in World War II held by France

- Otto Dix