Indian Ocean slave trade

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

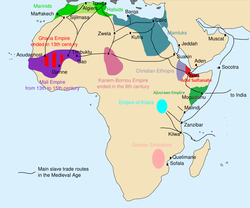

The Indian Ocean slave trade, sometimes known as the East African slave trade, involved the capture and transportation of predominately black African slaves along the coasts, such as the Swahili Coast and the Horn of Africa, and through the Indian Ocean. The areas impacted included East Africa, Southern Arabia, the west coast of India, Indian ocean islands (including Madagascar) and southeast Asia including Java.

The source of slaves was primarily in sub-saharan Africa, but also included other parts of Africa and the Middle East, Indian Ocean islands, as well as south Asia. While the slave trade in the Indian Ocean started 4,000 years ago, it expanded significantly in late antiquity (1st century CE) with the rise of Byzantine and Sassanid trading enterprises. Muslim slave trading started in the 7th century, with the volume of trade fluctuating with the rise and fall of local powers. Beginning in the 16th century, slaves were traded to the Americas, including Caribbean colonies, as Western European powers became involved in the slave trade. Trade declined with the abolition of slavery in the 19th century.[1][2]

History

[edit]Ancient Indian Ocean slave trade

[edit]Slave trading in the Indian Ocean goes back to 2500 BCE.[3] Ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Indians, and Persians all traded slaves on a small scale across the Indian Ocean (and sometimes the Red Sea).[4] Slave trading in the Red Sea around the time of Alexander the Great is described by Agatharchides.[4] Strabo's Geographica (completed after 23 CE) mentions Greeks from Egypt trading slaves at the port of Adulis and other ports in the Horn of Africa.[5] Pliny the Elder's Natural History (published in 77 CE) also describes Indian Ocean slave trading.[4]

In the 1st century CE, Periplus of the Erythraean Sea advised of slave trading opportunities in the region, particularly in the trading of "beautiful girls for concubinage."[4] According to this manual, slaves were exported from Omana (likely near modern-day Oman) and Kanê to the west coast of India.[4] The ancient Indian Ocean slave trade was enabled by building ships capable of carrying large numbers of human beings in the Persian Gulf using wood imported from India. These shipbuilding activities go back to Babylonian and Achaemenid times.[6]

Gujarati merchants evolved into the first explorers of the Indian Ocean as they traded slaves and African goods such as ivory and tortoise shells. The Gujaratis participated in the slavery business in Mombasa, Zanzibar and, to some extent, in the Southern African region.[7] Indonesians were also participants, and brought spices to trade in Africa. They would have returned via India and Sri Lanka with ivory, iron, skins, and slaves.[8]

After the Byzantine and Sasanian empires entered into slave trading in the 6th century AD, it became a major enterprise.[4]

Cosmas Indicopleustes wrote in his Christian Topography (550 CE) that Somali port cities were exporting slaves captured in the interior to Byzantine Egypt via the Red Sea.[5] He also mentioned the import of eunuchs by the Byzantines from Mesopotamia and India.[5] After the 1st century, the export of black Africans from Tanzania, Mozambique and other Bantu groups became a "constant factor".[6] Under the Sasanians, Indian Ocean trade supported not only the transport of slaves, but also of scholars and merchants.[4]

Muslim Indian Ocean slave trade

[edit]

The Muslim world expanded along trade routes, such as the silk route in the 8th century. As the power and size of the Muslim trading networks grew, merchants along the routes were motivated to convert to Islam, as this would grant them access to contacts, trade routes and favour regarding trading rules under Muslim governance. By the 11th century, Kilwa, on the coast of modern-day Tanzania, had become a fully-fledged affluent center of a Muslim-governed trade in slaves and gold.[9]

Exports of slaves to the Muslim world from the Indian Ocean began after Muslim Arab and Swahili traders won control of the Swahili Coast and sea routes during the 9th century (see Sultanate of Zanzibar). These traders captured Bantu peoples (Zanj) from the interior in the present-day lands of Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania and brought them to the coast.[10][11] There, the slaves gradually assimilated in the rural areas, particularly on the Unguja and Pemba islands.[12] Muslim merchants traded an estimated 1000 African slaves annually between 800 and 1700, a number that grew to c. 4000 during the 18th century, and 3700 during the period 1800–1870.[citation needed]

William Gervase Clarence-Smith writes that estimating the number of slaves traded has been controversial in the academic world, especially when it comes to the slave trade in the areas of the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea.[13]: 1 When estimating the number of people enslaved from East Africa, author N'Diaye and French historian Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau[14][15] estimate 8 million as the total number of people transported from the 7th century until 1920, amounting to an average of 5,700 people per year. Many of these slaves were transported by the Indian Ocean and Red Sea via Zanzibar.[16]

This compares with their estimate of 9 million people enslaved and transported via the Sahara. The captives were sold throughout the Middle East and East Africa. This trade accelerated as higher capacity ships led to more trade and greater demand for labour on plantations in the region. Eventually, tens of thousands of captives were being taken every year.[12][17][18]

Slave labor in East Africa was drawn from the Zanj, Bantu peoples that lived along the East African coast.[11][19] The Zanj were for centuries shipped as slaves by Muslim traders to all the countries bordering the Indian Ocean. The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs recruited many Zanj slaves as soldiers and, as early as 696, there were revolts of Zanj slave soldiers in Iraq.[20]

A 7th-century Chinese text mentions ambassadors from Java presenting the Chinese emperor with two Seng Chi (Zanj) slaves as gifts in 614. 8th and 9th century chronicles mention Seng Chi slaves reaching China from the Hindu kingdom of Sri Vijaya in Java.[20] The 12th-century Arab geographer al-Idrisi recorded that the ruler of the Persian island of Kish "raids the Zanj country with his ships and takes many captives."[21] According to the 14th-century Berber explorer Ibn Battuta, the sultans of the Kilwa Sultanate would frequently raid the areas around what is today Tanzania for slaves.[22]

The Zanj Rebellion, a series of uprisings that took place between 869 and 883 AD near the city of Basra (also known as Basara), situated in present-day Iraq, is believed to have involved enslaved Zanj who had originally been captured from the African Great Lakes region and areas further south in East Africa.[23] The rebellion grew to involve more than 500,000 slaves and free men who had been imported from across the Muslim empire and claimed "tens of thousands of lives in lower Iraq".[24]

The Zanj who were taken as slaves to the Middle East were often used in strenuous agricultural work.[25] As the plantation economy boomed and the Arabs became richer, they began to consider agriculture and other manual labor work as demeaning. The resulting labor shortage resulted in an increased slave market.

It is certain that large numbers of slaves were exported from eastern Africa; the best evidence for this is the magnitude of the Zanj revolt in Iraq in the 9th century, though not all of the slaves involved were Zanj. There is little evidence of what part of eastern Africa the Zanj came from, for the name is here evidently used in its general sense, rather than to designate the particular stretch of the coast, from about 3°N. to 5°S., to which the name was also applied.[26]

The Zanj were needed to cultivate:

the Tigris-Euphrates delta, which had become abandoned marshland as a result of peasant migration and repeated flooding, [and] [sic] could be reclaimed through intensive labor. Wealthy proprietors "had received extensive grants of tidal land on the condition that they would make it arable." Sugar cane was prominent among the crops of their plantations, particularly in Khūzestān Province. Zanj also worked the salt mines of Mesopotamia, especially around Basra.[27]

Their jobs were to clear away the nitrous topsoil that made the land arable. The working conditions were considered to be extremely harsh and miserable. Many other people were imported as slaves into the region, besides Zanj.[28]

Historian M. A. Shaban has argued that the rebellion was not a slave revolt, but a revolt of blacks (zanj). In his opinion, although a few runaway slaves did join the revolt, the majority of the participants were Arabs and free Zanj. He believes that if the revolt had been led by slaves, they would have lacked the necessary resources to combat the Abbasid government for as long as they did.[29]

In Somalia, the Bantu minorities are descended from Bantu groups who had settled in Southeast Africa after the initial expansion from Nigeria/Cameroon. To meet the demand for menial labor, Bantus from southeastern Africa captured by Somali slave traders were sold in cumulatively large numbers over the centuries to customers in Somalia and other areas in Northeast Africa and Asia.[30] People captured locally during wars and raids, mostly of Oromo and Nilotic origin, were also sometimes enslaved by Somalis.[31][32][33] However, the perception, capture, treatment and duties of these two groups of enslaved peoples differed markedly.[33][34]

From 1800 to 1890, between 25,000 and 50,000 Bantu slaves are thought to have been sold from the slave market of Zanzibar to the Somali coast.[35] Most of the slaves were from the Majindo, Makua, Nyasa, Yao, Zalama, Zaramo and Zigua ethnic groups of Tanzania, Mozambique and Malawi. Collectively, these Bantu groups are known as Mushunguli, which is a term taken from Mzigula, the Zigua tribe's word for "people" (the word holds multiple implied meanings including "worker", "foreigner", and "slave").[36]

14th-century traveler Ibn Battuta met a Syrian Arab girl from Damascus who was held as a slave of a black African governor in Mali. Ibn Battuta engaged in conversation with her in Arabic.[37][38][39][40][41] The black man was a scholar of Islam named Farba Sulayman. He was openly violating the rule in Islam against enslaving Arabs.[42][43]

Syrian girls were trafficked from Syria to Saudi Arabia until shortly before World War II. They were married to Arab men in order to legally bring them across the border but then divorced and given to other men. Syrians Dr. Midhat and Shaikh Yusuf were accused of engaging in this traffic of Syrian girls to supply them to Saudis.[44][45]

The Gulf of Bengal and Malabar in India were sources of eunuchs for the Safavid court of Iran, according to Jean Chardin.[46] Sir Thomas Herbert accompanied Robert Shirley in 1627-9 to Safavid Iran. He reported seeing Indian slaves sold to Iran, "above three hundred slaves whom the Persians bought in India: Persees, Ientews (gentiles [i.e. Hindus]) Bannaras [Bhandaris?], and others." brought to Bandar Abbas via ship from Surat in 1628.[47]

In the 1760s, the Arab Syarif Abdurrahman Alkadrie enslaved other Muslims en masse while raiding coastal Borneo in violation of sharia, before he founded the Pontianak Sultanate.[48]

Raoul du Bisson was traveling down the Red Sea when he saw the chief black eunuch of the Sharif of Mecca being brought to Constantinople for trial for impregnating a Circassian concubine of the Sharif and having sex with his entire harem of Circassian and Georgian women. The chief black eunuch had not been castrated correctly so he was still able to impregnate. Bisson reported that the women were drowned as punishment.[49][50][a] Twelve Georgian women were shipped to the Sharif to replace the drowned concubines.[51]

Emily Ruete (Salama bint Said) was born to Sultan Said bin Sultan and Jilfidan, a Circassian slave concubine (some accounts note her as Georgian[52][53][54]) a victim of the Circassian slave trade. An Indian girl slave named Mariam (originally Fatima) ended up in Zanzibar after being sold by multiple men. She originally came from Bombay. There were also Georgian girl slaves in Zanzibar.[55] Men in Egypt and Hejaz were customers for Indian women trafficked via Aden and Goa.[56][57]

Since Britain banned the slave trade in its colonies, 19th-century British-ruled Aden no longer legally received slaves. Those slaves sent from Ethiopia to Arabia were shipped to Hejaz instead for sale.[58]

Eunuchs, female concubines, and male laborers were the chief roles of slaves sent from Ethiopia to Jidda and other parts of Hejaz.[59] The southwest and southern parts of Ethiopia supplied most of the girls being exported by Ethiopian slave traders to India and Arabia.[60] Female and male slaves from Ethiopia made up the main supply of slaves to India and the Middle East.[61] Ethiopian slaves, both females imported as concubines and men imported as eunuchs, were imported in 19th-century Iran.[62][63] Sudan, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zanzibar exported the majority of slaves traded to 19th-century Iran.[64] The principal sources of these slaves, all of whom passed through Matamma, Massawa and Tadjoura on the Red Sea, were the southwestern parts of Ethiopia, in the Oromo and Sidama country.[13][page needed]

Both non-Muslims and Muslims in Southeast Asia during the end of the 19th century bought Japanese girls as slaves; they were imported by sea to the region.[65]

The Japanese women were sold as concubines to both Muslim Malay men and non-Muslim Chinese and British men of the British-ruled Straits Settlements of British Malaya. They had often been trafficked from Japan to Hong Kong and Port Darwin in Australia. In Hong Kong, the Japanese consul Miyagawa Kyujiro said these Japanese women were taken by Malay and Chinese men who "lead them off to wild and savage lands where they suffered unimaginable hardship." One Chinese man paid 40 British pounds for 2 Japanese women, and a Malay man paid 50 British pounds for a Japanese woman in Port Darwin, Australia after they were trafficked there in August 1888 by a Japanese pimp, Takada Tokijirō.[66][67][68][69][70][71]

The buying of Chinese girls in Singapore was forbidden for Muslims by a Batavia (Jakarta)-based Arab Muslim Mufti, Usman bin Yahya, in a fatwa. He ruled that in Islam it was illegal to buy free non-Muslims or marry non-Muslim slave girls during peace time from slave dealers, and non-Muslims could only be enslaved and purchased during holy war (jihad).[72]

Girls and women sold into prostitution from China to Australia, San Francisco, Singapore were ethnic Tanka people, and they served the men of the oversees Chinese community there.[73] The Tanka were regarded as a non-Han ethnicity during the Late Qing and Republican period of China.[74]

In Jeddah, Kingdom of Hejaz on the Arabian peninsula, the Arab king Ali bin Hussein, King of Hejaz had in his palace 20 Javanese girls from Java (modern day Indonesia). They were used as his concubines.[75]

The Saudi conquest of Hejaz led to the escape of many slaves from the city; this was where most slaves in Arabia were located. Muslims often ignored Islamic prohibitions against enslaving other Muslims. Arab slave traders fooled both Javanese Muslims and Javanese Christians, tricking them into sending their children to slavery by lying and promising to escort the children to different places. A 4- and 3-year-old pair of Javanese Muslim boys were enslaved after they were purportedly to be taken to Mecca to learn Islam. An Arab lied, claiming he would take a 10- and 8-year-old pair of Javanese Christian girls to family in Singapore, but enslaving them instead. Muslim men sometimes sold their own wives into slavery while on pilgrimage to Mecca, after pretending to be religious to trick the women into marrying them.[76]

The slave trade continued into the 20th century. Slavery in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and the United Arab Emirates did not end until the 1960s and 1970s. In the 21st century, activists contend that many immigrants who travel to those countries for work are held in virtual slavery

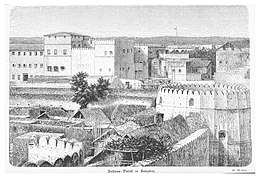

Zanzibar and expansion of slave trade in the Swaihili coast

[edit]The East African slave trade flourished greatly from the second half of the nineteenth century, when Said bin Sultan, an Oman Sultan, made Zanzibar his capital and expanded international commercial activities and plantation economy in cloves and coconuts. During this period demands for slaves grew drastically. The slaves were needed for local use mainly to work in plantations in Zanzibar and for export. Sultan Seyyid (seyyid is an Arabic title for Lord) Said made deliberate efforts to "revive old Arab-caravan trade" with mainland Africa, which became the major source of slaves.[77]

Said bin Sultan took six major initiatives which facilitated growth and expansion of his commercial empire. He firstly introduced a new currency “Maria Theresa Dollar” to supplement the exiting “Spanish Crown”, which simplified commercial activities. Secondly, he introduced a harmonized 5% import duty for any merchandise entering into his empire. He abolished export duties. Thirdly, he took advantage of Zanzibar's and Pemba's fertile soil to establish plantations of coconut and cloves. Fourthly, he revitalised and extended the "old Arab-caravan trade" with mainland East Africa to acquire slaves and ivory. He signed “commercial treaties with western capitalist countries, such as the United States of America in 1833, with Great Britain in 1839, and France in 1844. Finally, he invited Asian merchants and experts who dealt with financial matters.[78][79]

It was not until 1873 that Sultan Seyyid Barghash of Zanzibar, under pressure from Great Britain, signed a treaty that made the slave trade in his territories illegal.[80] The British played a significant role in ending slavery in East Africa. They made treaties with African rulers to stop the slave trade at its source and offered protection against slave kingdoms like Ashanti. The Royal Navy was instrumental in capturing slave ships and freeing enslaved Africans. Between 1808 and 1860, around 1,600 slave ships were captured, and more than 150,000 enslaved Africans were freed. Britain also made suppressing the Atlantic slave trade a part of its foreign policy.[81]

Arab Muslim traders also trafficked Malagasy and Comorian slaves from Madagascar and the Comorian Archipelago to ports on the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Swahili Coast, Zanzibar and the Horn of Africa. From 700AD to 1600AD, an estimated two to three thousand East African and Malagasy slaves were trafficked annually from the Indian Ocean coast to slave ports along the Red Sea and Southern Arabia. By the mid-1600s, this number had increased to five to six thousands slaves trafficked each year from Madagascar alone (not including the Comoros) to the Middle-east by non-European Muslim slave traders (Swahili, Comorian, Arab, Hadrami, Omani and Ottoman).[82]

Some historians estimate that during the 1600s as many as 150,000 Malagasy slaves were exported from Boeny in Northwest Madagascar to the Muslim World including the Red Sea Coast(Jeddah), Hejaz (Mecca), Arabia (Aden), Oman (Muscat), Zanzibar, Kilwa, Lamu, Malindi, Somalia (Barawa), and possibly Sudan (Suakin), Persia (Bandar Abbas), and India (Surat).[83] Given the unique racial composition of Madagascar, which was populated by a mix of Austronesian and Bantu settlers, the Malagasy slaves included people with Southeast Asian, African and hybrid phenotypes.

European traders participated in the lucrative slave trade between Madagascar and the Red Sea as well. In 1694, a Dutch East India Company (VOC) ship trafficked over 400 Malagasy slaves to an Arabian port on the Red Sea (presumably Jeddah) where they were sold to Arab Muslim traders to be further sold and enslaved in Mecca, Medina, Mocha, Aden, al-Shihr and Kishn.[84][85] At different times and to varying degrees, Portuguese, French, Dutch, English and Ottoman merchants were known to have taken part in the Malagasy slave trade too.

Singapore was also a destination for Vietnamese women trafficked from their villages. Many Vietnamese girls from Tonkin were disguised as Chinese when being trafficked out of Vietnam for prostitution.[86]

European Indian Ocean slave trade

[edit]The slave trade was taking place in the eastern Indian Ocean well before the Dutch settled there around 1600. The volume of this trade is unknown.[87]

The European slave trade in the Indian Ocean began when Portugal established Estado da Índia in the early 16th century. From then until the 1830s, c. 200 slaves were exported annually from Mozambique; similar figures have been estimated for slaves brought from Asia to the Philippines during the Iberian Union (1580–1640).

According to Francisco De Sousa, a Jesuit who wrote about it in 1698, Japanese slave girls were still owned by India-based Portuguese (Lusitanian) families long after the 1636 edict by Tokugawa Japan had expelled Portuguese people.[88]

The establishment of the Dutch East India Company in the early 17th century resulted in a quick increase in volume of the slave trade in the region; there were perhaps up to 500,000 slaves in various Dutch colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries in the Indian Ocean. For example, some 4000 African slaves were used to build the Colombo fortress in Dutch Ceylon. Bali and neighbouring islands supplied regional networks with c. 100,000–150,000 slaves 1620–1830. Indian and Chinese slave traders supplied Dutch Indonesia with perhaps 250,000 slaves during the 17th and 18th centuries.[87]

The East India Company (EIC) was established during the same period; in 1622 one of its ships carried slaves from the Coromandel Coast to Dutch East Indies. The EIC mostly traded in African slaves but also some Asian slaves purchased from Indian, Indonesian and Chinese slave traders. The French established colonies on the islands of Réunion and Mauritius in 1721; by 1735 some 7,200 slaves populated the Mascarene Islands, a number which had reached 133,000 in 1807.

The British captured the islands in 1810, however. Because the British had prohibited the slave trade in 1807, a system of clandestine slave trade developed to bring slaves to French planters on the islands; in all 336,000–388,000 slaves were exported to the Mascarane Islands from 1670 until 1848.[87]

In all, Europeans traders exported 567,900–733,200 slaves within the Indian Ocean between 1500 and 1850, and almost that same number were exported from the Indian Ocean to the Americas during the same period. The slave trade in the Indian Ocean was, nevertheless, very limited compared to c. 12,000,000 slaves exported across the Atlantic.[87][89] Some 200,000 slaves were sent in the 19th century to European plantations in the Western Indian Ocean.[13]: 10

Geography and transportation

[edit]- Estimates of slaves transported out of Africa, by route[90]

From the evidence of illustrated documents, and travelers' tales, people traveled on dhows or jalbas, Arab ships which were used as transport in the Red Sea.

To cross the Indian Ocean required better organization and more resources than overland transport. Ships coming from Zanzibar made stops on Socotra or at Aden before heading to the Persian Gulf or to India. Slaves were sold as far away as India, or China: a colony of Arab merchants operated in Canton. Serge Bilé cites a 12th-century text that said that most well-to-do families in Canton, China had black slaves. Although Chinese slave traders bought slaves (Seng Chi i.e. the Zanj[20]) from Arab intermediaries and "stocked up" directly in coastal areas of present-day Somalia, the local Somalis were not among the enslaved.[92] (These locals were referred to as Baribah and Barbaroi (Berbers) by medieval Arab and ancient Greek geographers, respectively (see Periplus of the Erythraean Sea),[19][93][94] and were no strangers to capturing, owning and trading slaves themselves.[95]

Slaves from other parts of East Africa made up an important commodity being transported by dhows to Somalia. During the 19th century, the East African slave trade grew enormously due to demands by Arabs, Portuguese, and French. Slave traders and raiders moved throughout eastern and central Africa to meet this rising demand. The Bantus inhabiting Somalia are descended from Bantu groups that had settled in Southeast Africa after the initial expansion from Nigeria/Cameroon. Their peoples were later captured and sold by traders.[34] The Bantus are ethnically, physically, and culturally distinct from Somalis, and they have remained marginalized ever since their arrival in Somalia.[96][97]

Towns and ports involved

[edit]

|

|

Gallery

[edit]-

Zanzibar Slave Market, 1860 - Stocqueler

-

Contemporary Engraving of Zanzibar Slave Market - World's Last Open Slave Market - Outside Anglican Cathedral - Stone Town - Zanzibar - Tanzania (8842023408)

-

Zanzibar Sklaven kewte RMG E9083

-

Servant or slave woman in Mogadishu

-

Slave-catching in the Indian Ocean (1873).

-

Slave-catching in the Indian Ocean (1873).

-

Capture of a Arab slave dhow by H. M. S. 'Penguin' off the Gulf of Aden - ILN 1867

-

Slave-catching in the Indian Ocean (1873).

-

Harper's weekly (1867) (14780409834)

-

Christian missions and social progress; a sociological study of foreign missions (1897) (14593517397)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Indian Ocean and Middle Eastern Slave Trades". obo. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Harries, Patrick (17 June 2015). "The story of East Africa's role in the transatlantic slave trade". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. p. 78.

The "globalized" Indian Ocean trade in fact has substantially earlier, even pre-Islamic, global roots. These roots extend back to at least 2500 BCE, suggesting that the so-called "globalization" of the Indian Ocean trading phenomena, including slave trading, was in reality a development that was built upon the activities of pre-Islamic Middle Eastern empires, which activities were in turn inherited, appropriated, and improved upon by the Muslim empires that followed them, and then, after that, they were again appropriated, exploited, and improved upon by Western European interveners.

- ^ a b c d e f g Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. pp. 81–82.

- ^ "'Even British were envious of Gujaratis'". The Times of India. 28 September 2013. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Beale, Philip. "From Indonesia to Africa:Borobudur Ship Expedition" (PDF).

- ^ Michalopoulos, Stelios; Naghavi, Alireza; Prarolo, Giovanni (1 December 2018). "Trade and Geography in the Spread of Islam". The Economic Journal. 128 (616): 3210–3241. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12557. ISSN 0013-0133. PMC 8046173. PMID 33859441.

- ^ Ochieng', William Robert (1975). Eastern Kenya and Its Invaders. East African Literature Bureau. p. 76. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ a b Bethwell A. Ogot, Zamani: A Survey of East African History, (East African Publishing House: 1974), p. 104

- ^ a b Lodhi, Abdulaziz (2000). Oriental influences in Swahili: a study in language and culture contacts. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. p. 17. ISBN 978-9173463775.

- ^ a b c Gervase Clarence-Smith, William, ed. (2013). The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135182144.

- ^ Lacoste, Yves (2005). "Hérodote a lu : Les Traites négrières, essai d'histoire globale, de Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau" [Book Review: African Slave Trade, an Attempted Global History, by Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau]. Hérodote (in French). 117 (117): 196–205. doi:10.3917/her.117.0193. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Pétré-Grenouilleau, Olivier (2004). Les Traites négrières, essai d'histoire globale [African Slave Trade, an Attempted Global History] (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2070734993.

- ^ "Focus on the slave trade". BBC. 3 September 2001. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- ^ Donnelly Fage, John; Tordoff, William (2001). A History of Africa (4 ed.). Budapest: Routledge. p. 258. ISBN 978-0415252485.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Edward R.; Dudley, Guilford (1973). A History of World Civilizations. Wiley. p. 615. ISBN 978-0471844808.

- ^ a b F.R.C. Bagley et al., The Last Great Muslim Empires, (Brill: 1997), p. 174

- ^ a b c Roland Oliver (1975). Africa in the Iron Age: c. 500 BC–1400 AD (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0521099004.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (1992). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Oxford University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-19-505326-5. OCLC 1022745387.

- ^ Gordon, Murray (1989). Slavery in the Arab World. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-941533-30-0. OCLC 1120917849.

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 585. ISBN 978-0313332739.

- ^ Asquith, Christina. "Revisiting the Zanj and Re-Visioning Revolt: Complexities of the Zanj Conflict – 868–883 Ad – slave revolt in Iraq". Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Islam, From Arab To Islamic Empire: The Early Abbasid Era". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Talhami, Ghada Hashem (1 January 1977). "The Zanj Rebellion Reconsidered". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 10 (3): 443–61. doi:10.2307/216737. JSTOR 216737.

- ^ "the Zanj: Towards a History of the Zanj Slaves' Rebellion". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ "Hidden Iraq". William Cobb. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ Shaban 1976, pp. 101–02.

- ^ Gwyn Campbell, The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, 1 edition, (Routledge: 2003), p. ix

- ^ Meinhof, Carl (1979). Afrika und Übersee: Sprachen, Kulturen, Volumes 62–63. D. Reimer. p. 272.

- ^ Bridget Anderson, World Directory of Minorities, (Minority Rights Group International: 1997), p. 456.

- ^ a b Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 116.

- ^ a b United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refugees Vol. 3, No. 128, 2002 UNHCR Publication Refugees about the Somali Bantu" (PDF). Unhcr.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Refugee Reports, November 2002, Volume 23, Number 8

- ^ Fisher, Humphrey J.; Fisher, Allan G. B. (2001). Slavery in the History of Muslim Black Africa (illustrated, revised ed.). NYU Press. p. 182. ISBN 0814727166.

- ^ Hamel, Chouki El (2014). Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam. Vol. 123 of African Studies. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1139620048.

- ^ Guthrie, Shirley (2013). Arab Women in the Middle Ages: Private Lives and Public Roles. Saqi. ISBN 978-0863567643.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2018). There and Back: Twelve of the Great Routes of Human History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199093564.

- ^ King, Noel Quinton (1971). Christian and Muslim in Africa. Harper & Row. p. 22. ISBN 0060647094.

- ^ Tolmacheva, Marina A. (2017). "8 Concubines on the Road: Ibn Battuta's Slave Women". In Gordon, Matthew; Hain, Kathryn A. (eds.). Concubines and Courtesans: Women and Slavery in Islamic History (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0190622183.

- ^ Harrington, Helise (1971). Adler, Bill; David, Jay; Harrington, Helise (eds.). Growing Up African. Morrow. p. 49.

- ^ Mathew, Johan (2016). Margins of the Market: Trafficking and Capitalism across the Arabian Sea. Vol. 24 of California World History Library. University of California Press. pp. 71–2. ISBN 978-0520963429.

- ^ "Margins Of The Market: Trafficking And Capitalism Across The Arabian Sea [PDF] [4ss44p0ar0h0]". vdoc.pub.

- ^ Babayan, Kathryn (15 December 1998). "EUNUCHS iv. THE SAFAVID PERIOD". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IX. pp. 64–69.

- ^ Floor, Willem (15 December 1988). "BARDA and BARDA-DĀRI iv. From the Mongols to the abolition of slavery". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. pp. 768–774.

- ^ Clarence-Smith, W. G. (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0195221516.

- ^ Remondino, Peter Charles (1891). History of circumcision, from the earliest times to the present Moral and physical reasons for its performance. Philadelphia; London: F. A. Davis. p. 101.

- ^ Junne, George H. (2016). The Black Eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire: Networks of Power in the Court of the Sultan. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 253. ISBN 978-0857728081.

- ^ Bisson, Raoul Du (1868). Les femmes, les eunuques et les guerriers du Soudan. E. Dentu. pp. 282–3.

- ^ Global Muslims in the Age of Steam and Print; From Zanzibar to Beirut by Jeremy Prestholdt, University of California Press, 2014, p.204

- ^ Connectivity in Motion: Island Hubs in the Indian Ocean World by Burkhard Schnepel, Edward A. Alpers, 2017, p.148

- ^ Balcony, Door, Shutter - Baroque heritage as materiality and biography in Stone Town, Zanzibar by Pamila Gupta, Vienna, 2019, p.14

- ^ Prestholdt, Jeremy (2008). Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization. Vol. 6 of California World History Library. University of California Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0520941472.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan A.C. (2020). Slavery and Islam. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1786076366.

- ^ "Slavery and Islam 4543201504, 9781786076359, 9781786076366". dokumen.pub.

- ^ Ahmed, Hussein (2021). Islam in Nineteenth-Century Wallo, Ethiopia: Revival, Reform and Reaction. Vol. 74 of Social, Economic and Political Studies of the Middle East and Asia. BRILL. p. 152. ISBN 978-9004492288.

- ^ Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (2013). The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-1135182212.

- ^ Yimene, Ababu Minda (2004). An African Indian Community in Hyderabad: Siddi Identity, Its Maintenance and Change. Cuvillier Verlag. p. 73. ISBN 3865372066.

- ^ Barendse, Rene J. (2016). The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 259. ISBN 978-1317458364.

- ^ Mirzai, Behnaz A. (2017). A History of Slavery and Emancipation in Iran, 1800-1929 (illustrated ed.). University of Texas Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1477311868.

- ^ Mirzai, Behnaz A. "A History of Slavery and Emancipation in Iran, 1800-1829" (PDF). media.mehrnews.com. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Scheiwiller, Staci Gem (2016). Liminalities of Gender and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Iranian Photography: Desirous Bodies. Routledge History of Photography (illustrated ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1315512112.

- ^ Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 0195221516.

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bill (26 August 2012). "Women, Overseas Sex Work and Globalization in Meiji Japan 明治日本における女性,国外性労働、海外進出". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. 10 (35).

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bill (1993). "The making of prostitutes: The Karayuki-san". Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. 25 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1080/14672715.1993.10408345.

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bin (19 March 1993). "The making of prostitutes: The Karayuki-san". Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. 25 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1080/14672715.1993.10408345.

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bill (2015). Sex in Japan's Globalization, 1870–1930: Prostitutes, Emigration and Nation-Building. Perspectives in Economic and Social History (reprint ed.). Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-1317322214.

- ^ Mihalopoulos, Bill (February 1998). "Modernization as creative problem making: Political action personal conduct and Japanese overseas prostitutes (La modernisation en tant que source de problème)". Economy and Society. 27 (1). Routledge: 50–73. doi:10.1080/03085149800000003. ISSN 0308-5147.

- ^ Mihapoulos, Bill (22 June 1994). "The making of prostitutes in Japan: the 'karayuki-san.' (Japan Enters the 21st Century)". Crime and Social Justice Associates.

- ^ Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195221516.

- ^ Hodge, Peter (1980). "or+among+Chinese+residents+as+their+concubines,+or+to+be+sold+for+export+to+Singapore,+San+Francisco,+or+Australia"&pg=PA34 Community Problems and Social Work in Southeast Asia: The Hong Kong and Singapore Experience. Hong Kong University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9622090222.

- ^ Luk, C. (2023). "The making of a littoral minzu: The Dan in late Qing–Republican intellectual writings". International Journal of Asian Studies. 20 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1017/S1479591421000401.

- ^ Proceedings of the 17th IAHA Conference. International Association of Historians of Asia. 2004. p. 151. ISBN 984321823X.

The anti - Husayn position was also taken by Idaran Zaman who reported that twenty beautiful young Javanese girls were found in the palace of his son, Sharif ' Ali in Jeddah. These girls were used as his concubines and were only ...

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (2004). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0203493021.

- ^ Coupland, Reginald (1967). The Exploitation of East Africa, 1856-1890: The Slave Trade and the Scramble. United States of America: Northwestern University Press.

- ^ Copland, Reginald (1967). The Exploitation of East Africa, 1856-1890. Northwestern University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Ingrams, W (2007). Zanzibar: Its History and Its People. London: Stacey International. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-905299-44-7.

- ^ "East Africa's forgotten slave trade – DW – 08/22/2019". dw.com. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Scanlan, Padraic (31 August 2021), "British Antislavery and West Africa", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.742, ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4, retrieved 17 April 2024

- ^ Mirzai, B.A.; Montana, I.M.; Lovejoy, Paul (2009). Slavery, Islam and Diaspora. Africa World Press. pp. 37–76.

- ^ Vernet, Thomas (17 February 2012). "Slave Trade and Slavery on the Swahili Coast, 1500–1750" (PDF). shs.hal.science/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2024.

- ^ "Subvoyage 5371". www.exploringslavetradeinasia.com. Exploring Slave Trade in Asia (ESTA). 2024. Archived from the original on 25 June 2024.

- ^ van Rossum, Matthias; de Windt, Mike (2018). References to Slave Trade in VOC Digital Sources, 1600-1800. Amsterdam: International Institute of Social History. p. 731. hdl:10622/YXEN6R.

- ^ Lessard, Micheline (2015). Human Trafficking in Colonial Vietnam. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-1317536222.

- ^ a b c d Allen 2017, Slave Trading in the Indian Ocean: An Overview, pp. 295–99

- ^ Kowner, Rotem (2014). From White to Yellow: The Japanese in European Racial Thought, 1300-1735. Vol. 63 of McGill-Queen's Studies in the History of Ideas (reprint ed.). McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 431, 432. ISBN 978-0773596849.

- ^ Copied content from Indian Ocean; see that page's history for attribution.

- ^ Saleh, Mohamed; Wahby, Sarah (30 March 2022). "Boom and Bust". Migration in Africa: 56–74. doi:10.4324/9781003225027-5. ISBN 978-1-003-22502-7.

- ^ Indian Ocean includes slaves transported through East Africa and the Red Sea

- ^ David D. Laitin, Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience, (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p. 52

- ^ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p. 13

- ^ James Hastings, Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 12: V. 12, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2003), p. 490

- ^ Henry Louis Gates, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p. 1746

- ^ "The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture – People". Cal.org. Retrieved 21 February 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ L. Randol Barker et al., Principles of Ambulatory Medicine, 7 edition, (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2006), p. 633

- ^ Abd Allah Pasha ibn Muhammad was the Sharif of Mecca during Raoul du Bisson's time in the Red Sea in 1863-5

Bibliography

[edit]- Allen, R. B. (2017). "Ending the history of silence: reconstructing European slave trading in the Indian Ocean" (PDF). Tempo. 23 (2): 294–313. doi:10.1590/tem-1980-542x2017v230206. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Shaban, M. A. (1976). Islamic History: A New Interpretation, Vol 2: A.D. 750-1055 (A.H. 132-448). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 100 ff. ISBN 978-0-521-21198-7.

- THE SLAVE-TRADE ON THE EAST COAST OF AFRICA. Shaw, Robert. The Anti-slavery reporter; London Vol. 19, Iss. 7, (Jun 1875): 173-175.