Stanley Matthews (judge)

Stanley Matthews | |

|---|---|

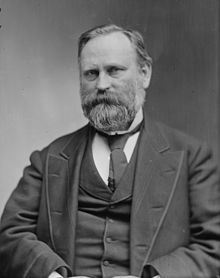

Stanley Matthews, by Mathew Brady, c. 1870-80 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office May 17, 1881[1] – March 22, 1889[1] | |

| Nominated by | James Garfield |

| Preceded by | Noah Haynes Swayne |

| Succeeded by | David J. Brewer |

| United States Senator from Ohio | |

| In office March 21, 1877 – March 3, 1879 | |

| Preceded by | John Sherman |

| Succeeded by | George H. Pendleton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Stanley Matthews July 21, 1824 Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | March 22, 1889 (aged 64) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Mary Ann Black

(m. 1843; died 1885)Mary K. Theaker

(m. 1886) |

| Children | 10, including Paul |

| Relatives | T. S. Matthews (grandson) |

| Education | Kenyon College (BA) |

| Signature | |

Thomas Stanley Matthews (July 21, 1824 – March 22, 1889), known as Stanley Matthews in adulthood,[2] was an American attorney, soldier, judge and Republican senator from Ohio who became an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from May 1881 to his death in 1889. A progressive justice,[citation needed] he was the author of the landmark rulings Yick Wo v. Hopkins and Ex parte Crow Dog

Early life and education

[edit]Matthews was born July 21, 1824, in Cincinnati, Ohio.[a] He was the oldest of 11 children born to Thomas J. Matthews and Isabella Brown Matthews (his second wife).[2]

He graduated from Kenyon College in 1840. While there he met future president of the United States Rutherford B. Hayes and close friend John Celivergos Zachos. Matthews moved to his hometown Cincinnati with Zachos. Zachos and Matthews were roommates. In Cincinnati Matthews studied law under Salmon P. Chase but he moved to Columbia, Tennessee, where he practiced law and edited the local newspaper from 1842 and 1844. Matthews returned to Cincinnati in 1844, and was admitted to the bar the following year.[2] In Cincinnati Matthews edited the antislavery newspaper Cincinnati Morning Herald and practiced law from 1853 to 1858.[4][5]

In 1849, Stanley Matthews, John Celivergos Zachos, Ainsworth Rand Spofford and 9 others founded the Literary Club of Cincinnati. One year later Rutherford B. Hayes became a member. Other prominent members included future President William Howard Taft and notable club guests Ralph Waldo Emerson, Booker T. Washington, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde and Robert Frost.[6]

Early legal career

[edit]Matthews was selected to serve as the clerk of the Ohio House of Representatives in 1848, and afterward served as a county judge in Hamilton County, Ohio. He was then elected to the Ohio State Senate for the 1st district, where he served from 1856 to 1858. He was then appointed as United States Attorney for the Southern District of Ohio, serving from 1858 to 1861.

Union officer

[edit]Matthews resigned as U.S. Attorney as the Civil War began, accepting a commission as lieutenant colonel with the 23rd Ohio Infantry regiment of the Union Army. His superior officer was future president Rutherford B. Hayes; future President William McKinley also served in the regiment. With the 23rd Ohio Regiment, Matthews fought at the battle of Carnifex Ferry. On October 26, 1861, he was appointed colonel of the 51st Ohio Infantry Regiment. and on April 11, 1862, he was nominated as brigadier general of U.S. Volunteers. However, the nomination was tabled and never confirmed. Nevertheless, Colonel Matthews commanded a brigade in the Army of the Ohio and later the Army of the Cumberland.

State judge, lawyer and politician

[edit]In 1863, after being elected a judge of the Superior Court of Cincinnati, Matthews resigned from the Union Army. Two years later, he returned to private practice. During the post-war reconstruction era, Matthews represented the railroad industry. His clients included Jay Gould.[7]

He ran for the United States House of Representatives in 1876, but was defeated. Then, in early 1877, he represented Rutherford B. Hayes before the electoral commission that Congress created to resolve the disputed 1876 presidential election.[7] That same year Matthews won a special election to the Senate to fill a vacancy created by the resignation of John Sherman. He did not seek reelection.

Associate justice

[edit]Matthews was initially nominated an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court on January 26, 1881, by President Hayes[8] in the last weeks of Hayes's presidency. The nomination ran into opposition in the U.S. Senate because of Matthews's close ties to railroad interests and due to his close long-term friendship with Hayes. Consequently, the Judiciary Committee took no action on the nomination during the remainder of the 46th Congress.[9][10]

On March 14, 1881, 10 days after taking office, President James A. Garfield re-nominated Matthews to the Court.[8] Though a new nomination from a new president, earlier concerns about Matthews's suitability for the Court persisted, and Garfield was widely criticized for re-submitting Matthews's name.[9] In spite of the opposition, and, although the Judiciary Committee made a recommendation to the Senate that it reject the nomination,[11] on May 12, the Senate voted 24–23 to confirm Matthews. The vote was the closest for any successful Supreme Court nominee in U.S. Senate history;[b] no other justice has been confirmed by a single vote.[8][10][13]

Matthews's tenure as a member of the Supreme Court began on May 17, 1881, when he took the judicial oath, and ended March 22, 1889, upon his death.[1][7] He was regarded as one of the more progressive justices on the Court at the time.[13]

Yick Wo v. Hopkins

[edit]In 1880, the city of San Francisco, California passed an ordinance that persons could not operate a laundry in a wooden building without a permit from the Board of Supervisors. The ordinance conferred upon the Board of Supervisors the discretion to grant or withhold the permits. At the time, about 95% of the city's 320 laundries were operated in wooden buildings. Approximately two-thirds of those laundries were owned by Chinese persons. Although most of the city's wooden building laundry owners applied for a permit, none were granted to any Chinese owner, while virtually all non-Chinese applicants were granted a permit. Yick Wo (益和, Pinyin: Yì Hé, Americanization: Lee Yick), who had lived in California and had operated a laundry in the same wooden building for many years and held a valid license to operate his laundry issued by the Board of Fire-Wardens, continued to operate his laundry and was convicted and fined $10.00 for violating the ordinance. He sued for a writ of habeas corpus after he was imprisoned in default for having refused to pay the fine.

The Court, in a unanimous opinion written by Justice Matthews, found that the administration of the statute in question was discriminatory and that there was therefore no need to even consider whether the ordinance itself was lawful. Even though the Chinese laundry owners were usually not American citizens, the court ruled they were still entitled to equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. Justice Matthews also noted that the court had previously ruled that it was acceptable to hold administrators of the law liable when they abused their authority. He denounced the law as a blatant attempt to exclude Chinese from the laundry trade in San Francisco, and the court struck down the law, ordering dismissal of all charges against other laundry owners who had been jailed.

Personal life

[edit]In 1843, Matthews married Mary Ann "Minnie" Black. They had 10 children, four of whom died during an outbreak of scarlet fever in 1859.[2] Over a three-week period, the outbreak claimed the lives of their three eldest sons (nine-year-old Morrison, six-year-old Stanley, and four-year-old Thomas) as well as younger daughter Mary (age two-and-a-half). Oldest daughter Isabella (seven at the time) and baby William Mortimer survived the devastating outbreak, although Isabella would die in 1868 at the age of sixteen. Their four younger children (Grace, Eva, Jane, and another son named Stanley, later called Paul) were born after the scarlet fever outbreak.[14]

"Minnie" died in Washington, D.C., on January 22, 1885, at age 63.[15] Matthews married Mary K. Theaker, widow of Thomas Clarke Theaker, on June 23, 1886, in New York.[16]

Death and legacy

[edit]Matthews's health declined precipitously during 1888; he died in Washington, D.C., on March 22, 1889.[17][18] He was survived by second wife Mary, as well as five of his children with Minnie: Mortimer, Grace, Eva, Jane, and Paul.[19] He is interred at Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio.[20][21]

Daughter Jane Matthews married her late father's colleague on the Court, Associate Justice Horace Gray, on June 4, 1889.[22] Daughter Eva Lee Matthews became a schoolteacher and monastic, founding the Community of the Transfiguration, which engaged in charity work in Ohio, Hawaii and in China, leading to her liturgical commemoration in the Episcopal Church.[23] Son Paul Clement was bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey from 1915 to 1937. His son, Justice Matthews's grandson, Thomas Stanley, was editor of Time magazine from 1949 to 1953.[24][25]

A collection of Justice Matthews's correspondence and other papers is located at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center library in Fremont, Ohio and open for research. Additional papers and collections are at: Cincinnati Historical Society, Cincinnati, Ohio; Library of Congress, Manuscript and Prints & Photographs Divisions, Washington, D.C.; Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio; Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, New York; State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Archives Division, Madison, Wisconsin; and Mississippi State Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi.[26]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Supreme Court of Ohio & Ohio Judicial System website lists his birthplace as Lexington, Kentucky.[3]

- ^ In percentage terms, the 50–48 vote in 2018 confirming Brett Kavanaugh was slightly closer than Matthews's. Matthews received 51.06% of the vote to Kavanaugh's 51.02%.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Justices 1789 to Present". supremecourt.gov. Archived from the original on April 15, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Cushman, Clare, ed. (2013). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–2012 (Third ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: CQ Press. pp. 203–206. ISBN 978-1-60871-832-0. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ "Stanley Matthews (July 21, 1824 - March 22, 1889)". supremecourt.ohio.gov. Columbus, Ohio: Supreme Court of Ohio. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ "Topping, Eva Catafygiotu" Archived August 31, 2021, at the Wayback Machine John Zachos Cincinnatian from Constantinople The Cincinnati Historical Society Bulletin Volumes 33-34 Cincinnati Historical Society 1975: p. 51

- ^ "Stanley Matthews". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ Topping, 1975, p. 54

- ^ a b c "Stanley Matthews, 1881-1889". supremecourthistory.org. Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Senate: Supreme Court Nominations: 1789–Present". senate.gov. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Senate. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Sheldon (October 6, 2018). "A look at the closest Court confirmation ever". Constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: National Constitution Center. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Hogue, Henry H. (August 20, 2010). "Supreme Court Nominations Not Confirmed, 1789-August 2010" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress (RL31171). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2006. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ McMillion, Barry J.; Rutkus, Denis Steven (July 6, 2018). "Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress (RL33225). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Keller, Chris (October 6, 2018). "Senate vote on Kavanaugh was historically close". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Phillips, Kristine (October 8, 2018). "'Moral dry-rot': The only Supreme Court justice who divided the Senate more than Kavanaugh". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Przybyszewski, Linda (2017). "Scarlet Fever, Stanley Matthews, and the Cincinnati Bible War". Journal of Supreme Court History. 42 (3): 256–274. doi:10.1111/jsch.12153. ISSN 1540-5818. S2CID 149056812.

- ^ "OBITUARY. Mrs Mary A Matthews". The Indianapolis News. January 22, 1885. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2020 – via Hoosier State Chronicles.

- ^ "United by Marriage. Justice Stanley Matthews Taking a Wife". The New York Times. June 24, 1886. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Dead Justice.; Funeral Services Of Stanley Matthews In Washington". The New York Times. March 26, 1889. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Stanley Matthews. A Member of the Supreme Court Bench Dead. An Able Jurist And Judge". Los Angeles Herald. March 23, 1889. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2019 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside.

- ^ "Justice Matthews Dead". Washington Post. March 23, 1889. p. 2.

- ^ "Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook". Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2013. Supreme Court Historical Society.

- ^ Christensen, George A., "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited", Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17–41 (February 2008), University of Alabama.

- ^ Massachusetts.; Bar Association of the City of Boston. (1903). Proceedings of the bar and of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in memory of Horace Gray, January 17, 1903. Boston: [s.n.] p. 10. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ "Eva Lee Matthews". Archived from the original on July 6, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ "T. S. Matthews Papers 1910-1991". Princeton University. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa W. (January 6, 1991). "T. S. Matthews, 89, Ex-Editor of Time and Author". The New York Times. p. 22. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Location of papers, Sixth Circuit Archived 2009-01-19 at the Wayback Machine United States Court of Appeals.

Further reading

[edit]- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Bibliography, biography and location of papers, Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Furer, Howard B., ed. (1986). The Fuller Court, 1888-1910. (The Supreme Court in American Life Series.). New York: Associated Faculty Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-86733-060-1.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Stephenson, Donald Grier Jr. (2003). The Waite Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN 1-57607-829-9. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "Stanley Matthews (id: M000255)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- Stanley Matthews at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- Stanley Matthews at Oyez, a project of the Illinois Institute of Technology's Chicago-Kent College of Law. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- "Stanley Matthews". Find a Grave. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- 1824 births

- 1889 deaths

- 19th-century American newspaper editors

- 19th-century American judges

- American male journalists

- American Presbyterians

- Burials at Spring Grove Cemetery

- Judges of the Superior Court of Cincinnati

- Kenyon College alumni

- Ohio Democrats

- Ohio lawyers

- Ohio Libertyites

- Ohio Republicans

- Ohio state court judges

- Ohio state senators

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- Politicians from Cincinnati

- Republican Party United States senators from Ohio

- Tennessee lawyers

- Union army officers

- United States Attorneys for the Southern District of Ohio

- United States federal judges appointed by James A. Garfield

- Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Half-Breeds (Republican Party)