Bath, New Hampshire

Bath, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

Town | |

The Brick Store, built 1824 | |

| Motto: "Covered Bridge Capital of New England" | |

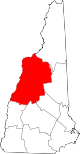

Location in Grafton County, New Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 44°10′01″N 71°57′58″W / 44.16694°N 71.96611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Grafton |

| Incorporated | 1761 |

| Villages | Bath Swiftwater Upper Village |

| Government | |

| • Board of Selectmen |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 38.6 sq mi (99.9 km2) |

| • Land | 37.7 sq mi (97.7 km2) |

| • Water | 0.8 sq mi (2.2 km2) 2.23% |

| Elevation | 530 ft (162 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 1,077 |

| • Density | 28/sq mi (11.0/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP codes | 03740 (Bath) 03785 (Woodsville) |

| Area code | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-03940 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0873540 |

| Website | www |

Bath is a town in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 1,077 at the 2020 census,[2] unchanged from the 2010 census.[3] Now a tourist destination and commuter town for Littleton, the town is noted for its historic architecture, including the Brick Store and three covered bridges. Bath includes the village of Swiftwater and part of the district known as Mountain Lakes.

History

[edit]

The town was granted to the Rev. Andrew Gardner and 61 others on September 10, 1761, by Governor Benning Wentworth, who named it for William Pulteney, 1st Earl of Bath. It was first settled in 1765 by John Herriman from Haverhill, Massachusetts.[4] But the terms of the original grant were unfulfilled, so Bath was regranted on March 29, 1769, by Governor John Wentworth. The first census, taken in 1790, recorded 493 residents.[5]

Situated at the head of navigation on the Connecticut River, and shielded from strong winds by the Green Mountains to the west and White Mountains to the east, Bath soon developed into "...one of the busiest and most prosperous villages in northern New Hampshire."[5] Intervales provided excellent alluvial soil for agriculture, and the Ammonoosuc and Wild Ammonoosuc rivers supplied water power for mills. The population reached 1,627 in 1830, when 550 sheep grazed the hillsides.[4] A vein of copper was mined. The White Mountains Railroad up the Ammonoosuc River valley opened August 1, 1853, shipping Bath's lumber, potatoes, livestock and wood pulp. By 1859, the town had two gristmills and two sawmills.[6] Other industries would include a woolen mill, creamery, distillery and two starch factories.[7]

A disastrous fire swept through Bath village on February 1, 1872, destroying the Congregational church, Bath Hotel and several dwelling houses. The church was rebuilt in 1873.[8] By 1874, Bath was served by the Boston, Concord and Montreal and White Mountains (N.H.) Railroad.[8]

But nearby Woodsville in the town of Haverhill developed into a major railroad junction, and the region's commercial center shifted there. By 1886, once thriving Bath was described as in decay.[5] But this economic dormancy of the Victorian era preserved much early architecture in the village, particularly in the Federal and Greek Revival styles. The Brick Store, built in 1824 and designed by Alexander Parris, dominated the town center until its closure in 2020.[9] Bath's Upper Village features a cluster of Federal-style houses based on the handbook designs of architect Asher Benjamin.[10]

Geography

[edit]Bath is in northwestern New Hampshire, in the northern part of Grafton County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 38.6 square miles (99.9 km2), of which 37.7 square miles (97.7 km2) are land and 0.85 square miles (2.2 km2) are water, comprising 2.23% of the town.[1] The Connecticut River forms the western boundary of the town; the Ammonoosuc and Wild Ammonoosuc rivers flow through the town. Bath lies fully within the Connecticut River watershed.[11] The highest points in Bath are a trio of knobs on Gardner Mountain, all found near the northernmost point in town and all measuring slightly greater than 1,980 feet (600 m) above sea level.

Geologically, Bath is located at the northernmost extent of former Lake Hitchcock, a post-glacial lake that shaped the Connecticut River valley from this point south to Middletown, Connecticut.[12]

The town is crossed by U.S. Route 302 and New Hampshire Route 112. The village of Swiftwater is located along Route 112, near the town's boundary with Haverhill.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 498 | — | |

| 1800 | 825 | 65.7% | |

| 1810 | 1,316 | 59.5% | |

| 1820 | 1,498 | 13.8% | |

| 1830 | 1,627 | 8.6% | |

| 1840 | 1,591 | −2.2% | |

| 1850 | 1,574 | −1.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,366 | −13.2% | |

| 1870 | 1,168 | −14.5% | |

| 1880 | 1,032 | −11.6% | |

| 1890 | 935 | −9.4% | |

| 1900 | 1,006 | 7.6% | |

| 1910 | 978 | −2.8% | |

| 1920 | 838 | −14.3% | |

| 1930 | 785 | −6.3% | |

| 1940 | 686 | −12.6% | |

| 1950 | 706 | 2.9% | |

| 1960 | 604 | −14.4% | |

| 1970 | 607 | 0.5% | |

| 1980 | 761 | 25.4% | |

| 1990 | 784 | 3.0% | |

| 2000 | 893 | 13.9% | |

| 2010 | 1,077 | 20.6% | |

| 2020 | 1,077 | 0.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[2][13] | |||

As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 893 people, 350 households, and 253 families residing in the town. The population density was 23.4 inhabitants per square mile (9.0/km2). There were 450 housing units at an average density of 11.8 per square mile (4.6/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 99.33% White, 0.22% African American, 0.22% Native American, and 0.22% from two or more races.

There were 350 households, out of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.4% were married couples living together, 6.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.7% were non-families. 21.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.55 and the average family size was 2.96.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 24.3% under the age of 18, 6.7% from 18 to 24, 24.2% from 25 to 44, 29.2% from 45 to 64, and 15.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.1 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $43,088, and the median income for a family was $47,000. Males had a median income of $27,679 versus $22,167 for females. The per capita income for the town was $17,916. About 2.8% of families and 5.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.5% of those under age 18 and 5.5% of those age 65 or over.

Sites of interest

[edit]Notable sites within Bath include:

- The Brick Store (NRHP, 1985)

- Covered bridges:

- Bath Covered Bridge (NRHP, 1976)

- Haverhill–Bath Covered Bridge (NRHP, 1977)

- Swiftwater Covered Bridge (NRHP, 1976)

- Goodall-Woods Law Office (NRHP, 1980)

- Jeremiah Hutchins Tavern (NRHP, 1984)

- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 121: Bath, New Hampshire

- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 217: Bath Bridge

Notable people

[edit]- Timothy Bedel (1737–1787), mill owner, military commander[15]

- Raymond S. Burton (1939–2013), longest-serving Executive Councilor in New Hampshire history

- Henry Hancock (1822–1883), lawyer, land surveyor

- Harry Hibbard (1816–1872), US congressman

- James Hutchins Johnson (1802–1887), businessman, militia officer, US congressman

- Patti Page (1927–2013), singer

- E. Carleton Sprague (1822–1895), former New York state senator

- Lillian Carpenter Streeter (1854–1935), social reformer, clubwoman, author

References

[edit]- ^ a b "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files – New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Bath town, Grafton County, New Hampshire: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ United States Census Bureau, American FactFinder, 2010 Census figures. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Hayward's Gazetteer of New England 1839

- ^ a b c Hamilton Child, History of Bath, Gazetteer of Grafton County, N.H., 1709–1886; Syracuse, New York 1886

- ^ Austin J. Coolidge & John B. Mansfield, A History and Description of New England; Boston, Massachusetts 1859

- ^ "Bath: A Short History". Archived from the original on November 13, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

- ^ a b Article in Statistics and Gazetteer of New-Hampshire (1875)

- ^ "Brick Store Closing Has Ripple Effect". Caledonian Record. July 16, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ New Hampshire History & Heritage Guide

- ^ Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ "Connecticut River". Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ David Library of the American Revolution: Timothy Bedel Papers Retrieved August 18, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Hudson, Marshall (July 19, 2018). "Mercy's Garden". New Hampshire. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

The legend (or legends) behind one of the oddest vegetable plots in the state.

- Ammonoosuc Rail Trail, between Woodsville and Littleton via Wayback Machine